Very simply stated, a concept is an idea that underpins your project. To an architect, the concept is what distinguishes a work of architecture from a mere building. At its core, architecture seeks to solve problems. It’s the questions we ask that will determine which problems our architecture will solve. Developing a concept allows us to frame the questions we’re asking and it guides the design process. Choosing the starting point for your design can be intimidating and an early stumbling block for designers of any skill level. But it doesn’t have to be.

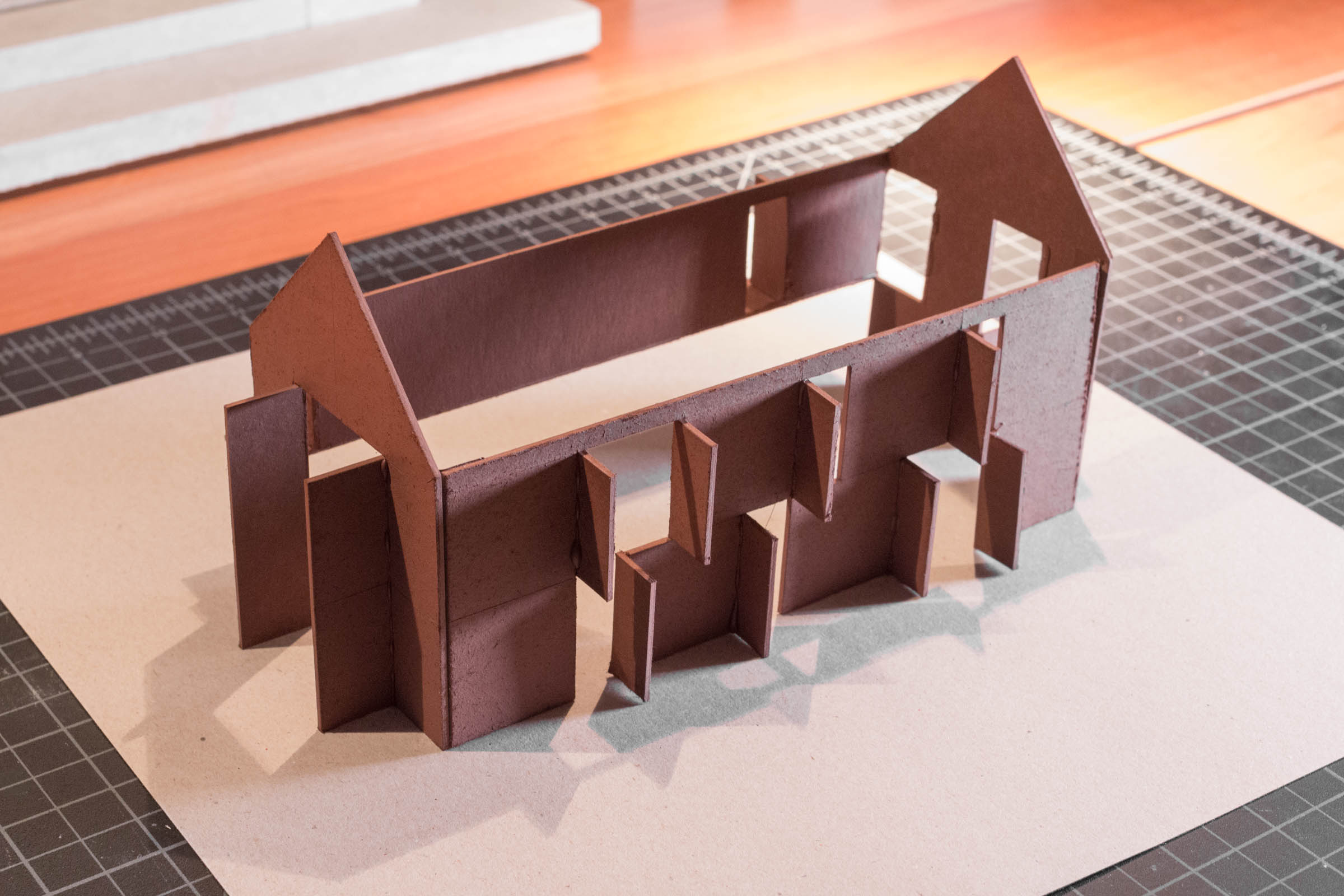

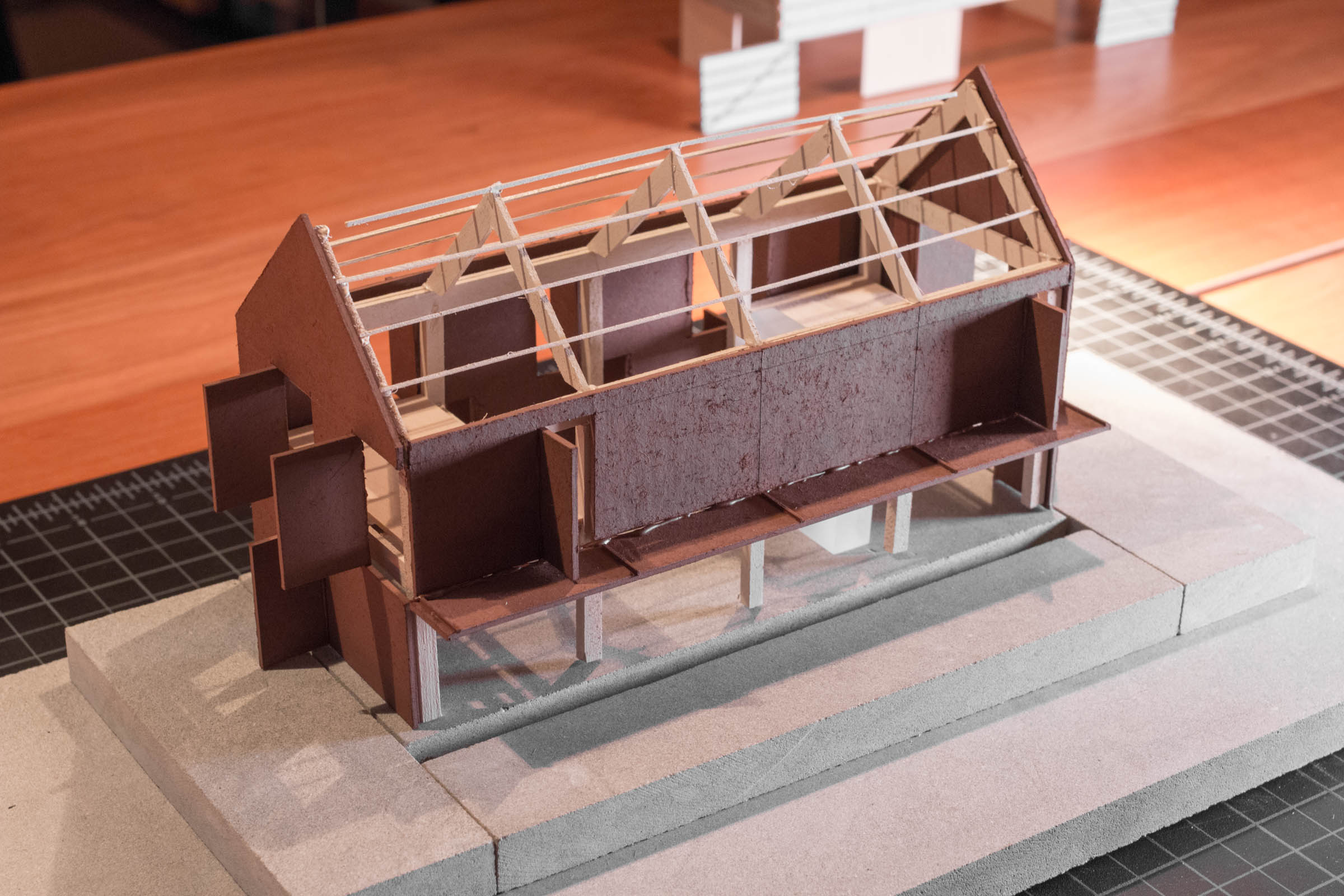

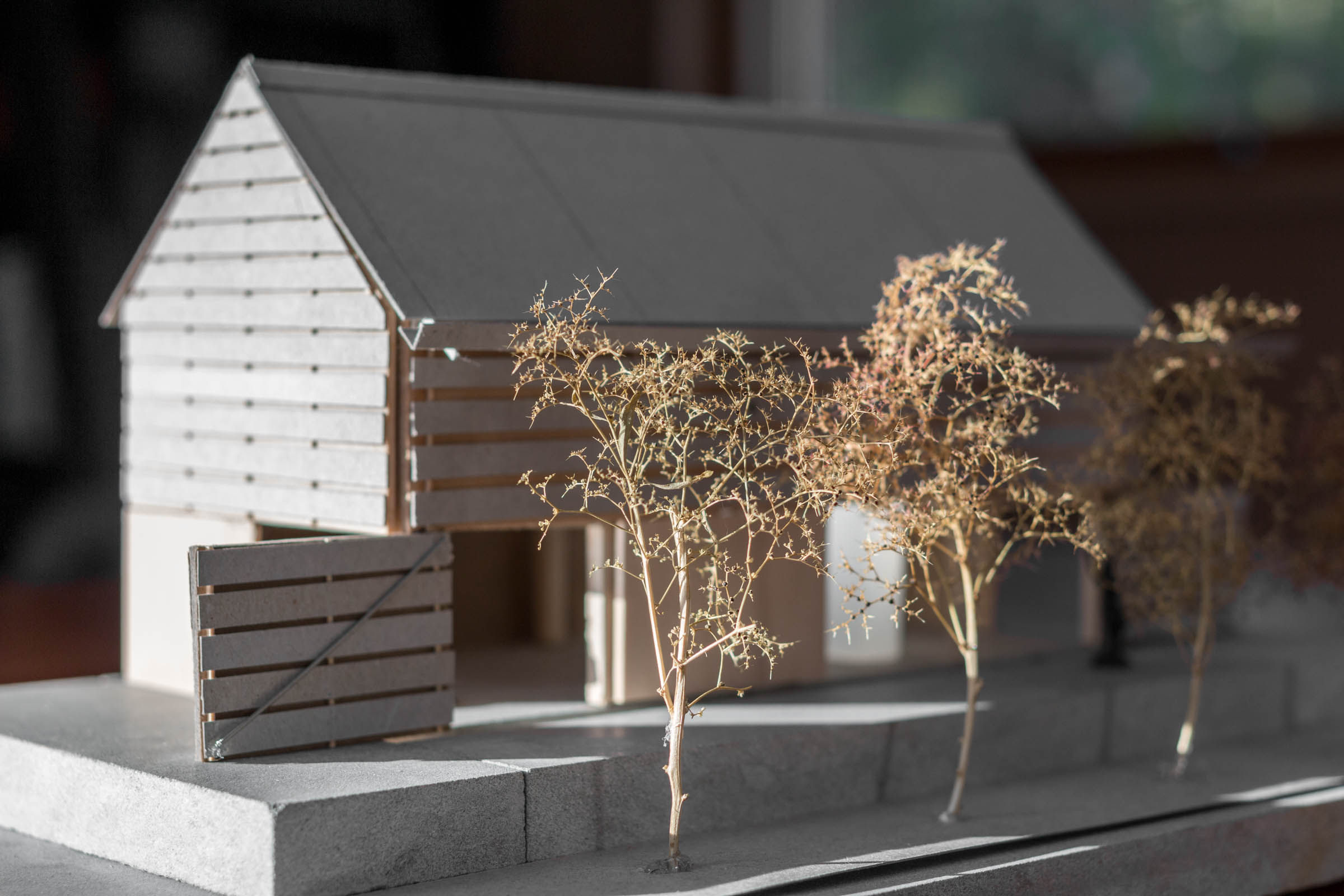

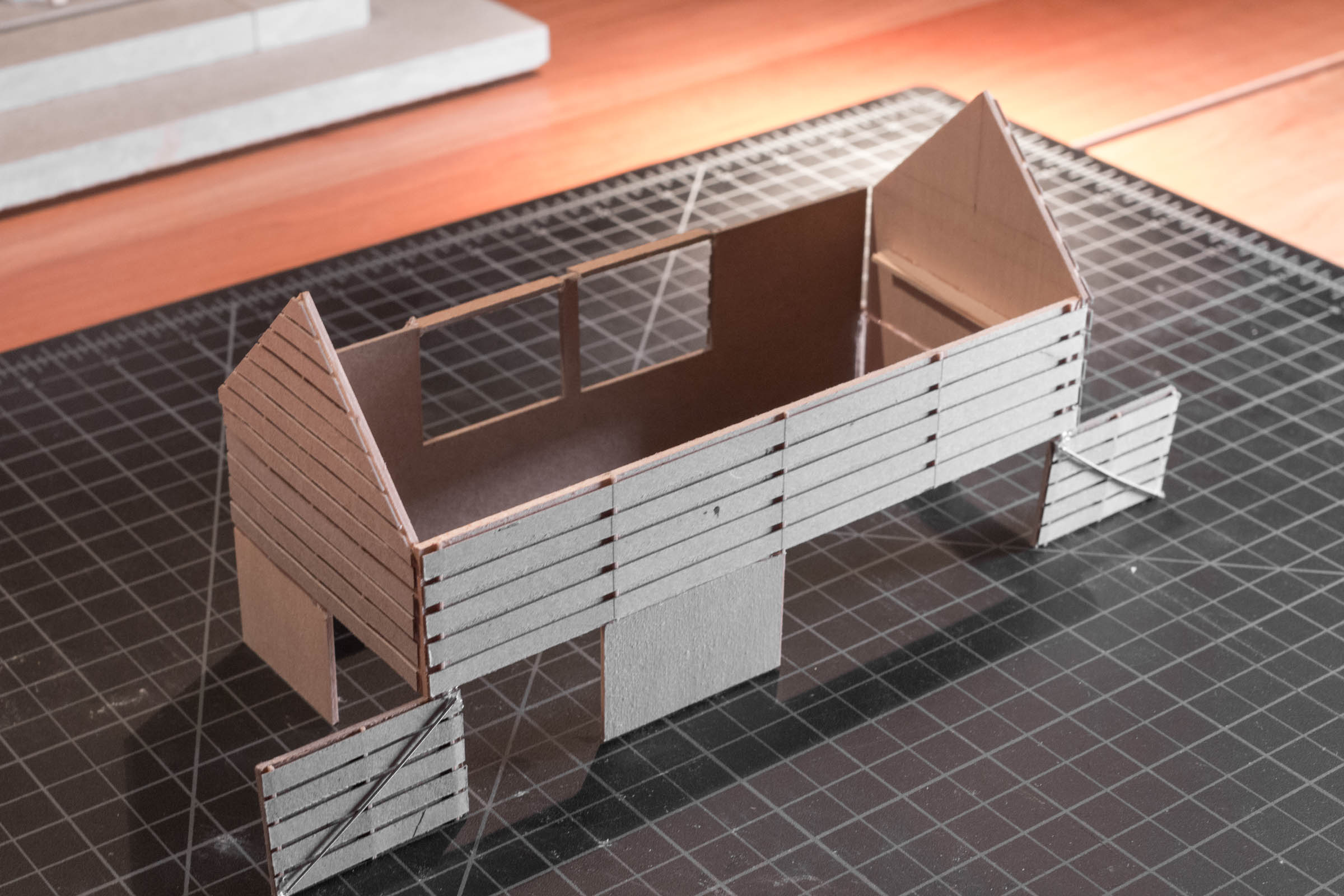

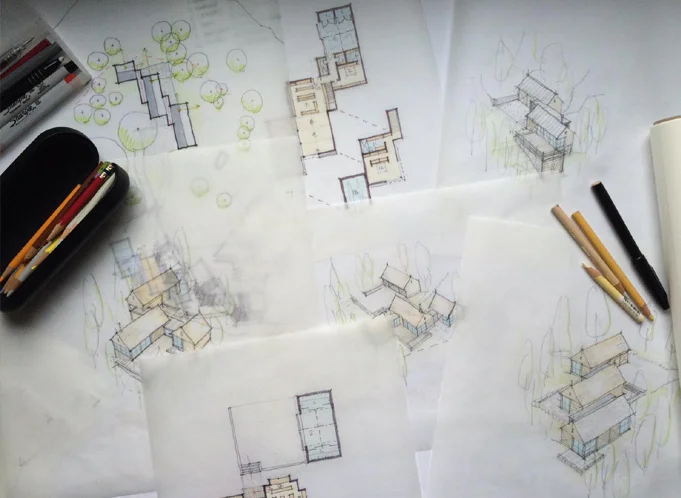

A concept shouldn’t be rigorous; the more malleable it is, the better. In fact, most architecture can’t be reduced to one singular concept diagram rather it’s informed by many concepts working in concert. There may be organizational concepts, material concepts, functional, or structural or formal concepts. Don’t fret if your design idea isn’t reducible to a single elegant black stroke on the page. It’s best to illustrate concept development with a real project as I said. So, we’ll use our Squid Cove Residence as an example. Before we can develop the concept, we have to first understand the practical constraints.

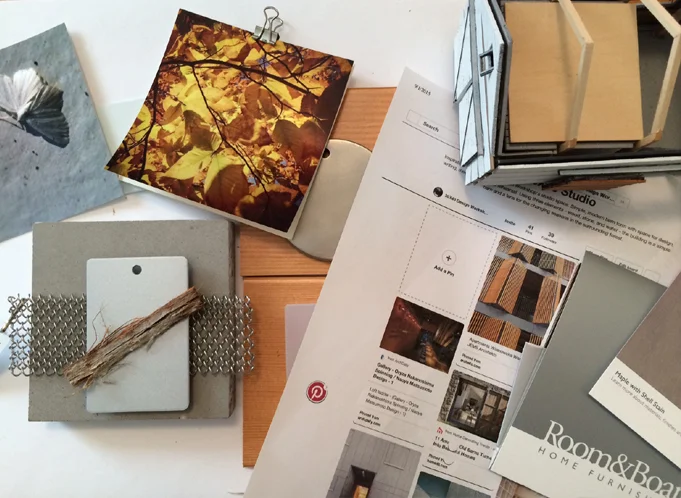

My design process begins only after gathering and assessing all the given parameters for a project. Now, this primarily consists of three types of information. There’s information derived from the site - things like: local climate, the prevailing winds, the solar aspect, vegetation, neighboring structures, the site’s history, and any unique liabilities or opportunities. The site of course also comes along with legal frameworks for development, which describe where and what we can and can’t build. The second type of information we’ll gather is from the client. Every client has a set of cultural beliefs and preconceptions, preferences and agendas. Of course, we’ll want to determine their budget, and understand the personality traits and organizational politics which might also shape the design. The client and the building type together determine what architects call, “the program” which is essentially a detailed accounting of all the spaces the building will contain.

And, the third type of information I gather is related to the building typology – is it a museum, a home…or a school for example? To learn about a building typology we often conduct an analysis of notable or relevant historical precedents. We want to know the essential problems these types of structures grapple with. Understanding the history of the archetype allows us to approach a problem from a fresh perspective. All of this is necessary information that we collect for every project. This inventory can also serve as the progenitor for the design concept – our seed idea. Rather than shunting creativity, these constraints often incite the creative process.

As with a good film, the setting, the characters, the cinematography, and the plot all conspire to make it what it is. It’s the experience you’ll recall rather than the concept per se. Sure, the concept sets the film in motion and it’s the starting point for all that follows. But this concept – the one or two-line description – can’t possible capture the richness and depth of the finished film…or in our case the architecture. Yet without it, the work is unfulfilling and so it should be clear that the concept is necessary for all our work as architects.

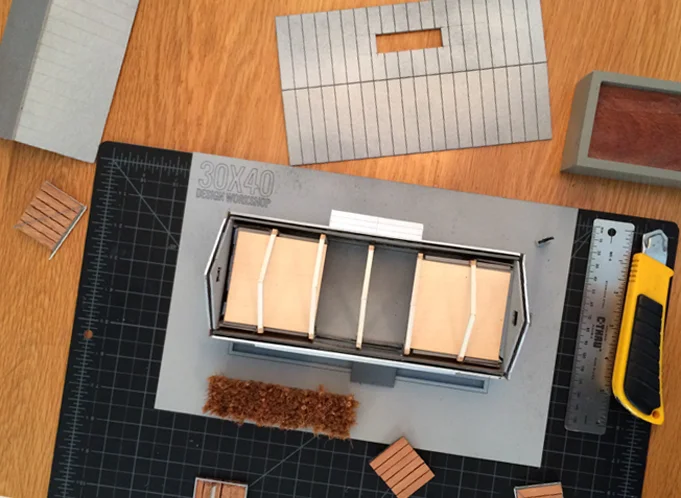

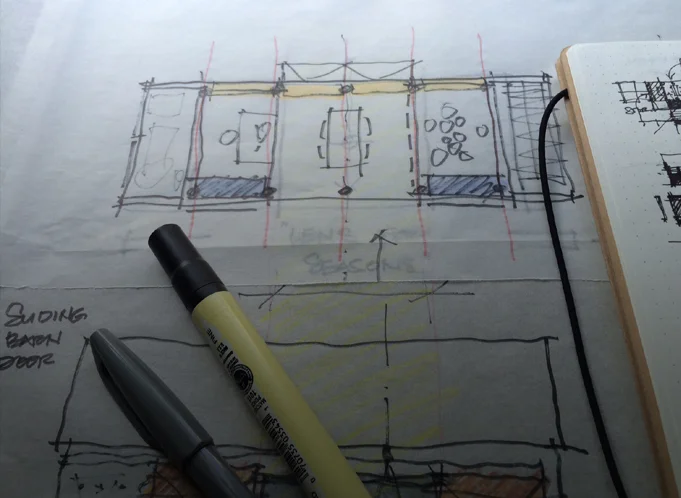

Be sure to watch the video for an inside look at how I craft an abstract idea into a home.