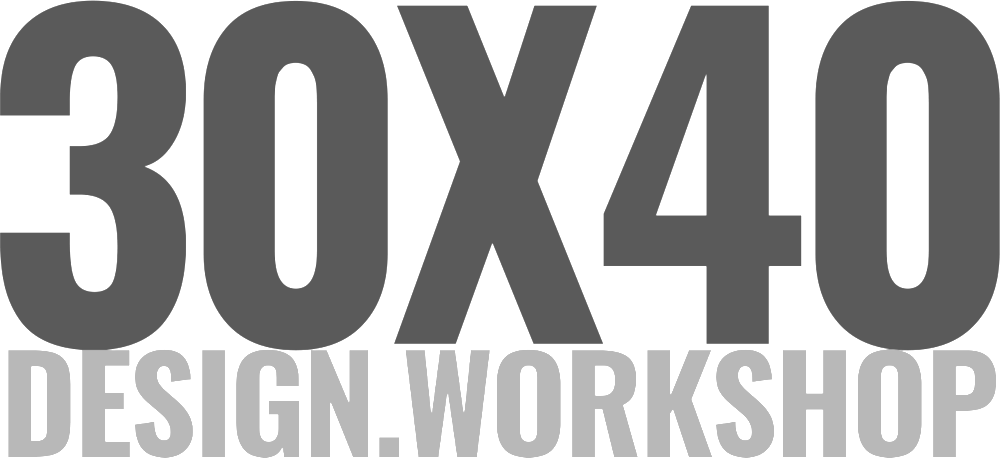

We all want to use our time efficiently and minimize effort spent on the administrative side of our design practice. Searching endless folders or open tabs for links to products you swore you found last week, trying to recall the milestones you agreed to or where the current Gantt chart lives and share it with the team isn’t a good use of anyone’s time.

I use Notion for all of this and more.

Notion has served as a second brain for me for a few years now; it’s the best “all-in-one-productivity and project management tool” I’ve found for both personal and professional documentation. It’s intuitive, capable and infinitely flexible; a blank canvas that can be almost anything you want. The open-ended structure is a strength when you know how to use it, but can be a little intimidating when you're just getting started and unsure of how to set up your workspace.

If you’re unfamiliar with it, watch the videos below to get set up; continue reading if you’re already using it see how I’ve set my workspace to run my design practice.

Getting Organized

Every Sunday I plan my Weekly schedule which is simply a favorited page that resides in the upper left corner of my workspace. I use the Maker’s Schedule + Manager’s Schedule as the structure for the week to keep me on-task. Also notice the annual objectives (set in the video above) are just a click away and serve as a reminder of the bigger goals and priorities I’m working toward each year.

I used to live in my inbox with the window open and collecting emails all day long. Every notification lured me back to the inbox, wasting my time and distracting me from the deep work that needed doing. The work that would push my business and projects forward. Maybe you can relate?

Using Notion has changed that. Now, I live in my “Week of” board which makes explicit the priorities I’ve set on Sunday rather than my inbox which is filled with the priorities of others.

Week Of Schedule Page (click the image to enlarge)

Below the schedule, I keep two to-do lists, one related to home the other for the business and a task table which is linked to my calendar. This is a great place to catalog recurring tasks you might otherwise neglect: like your annual architecture license renewal, LLC document filings, annual reports, etc. I also use it to schedule my regular monthly invoicing, which is something I’ve been getting better at over the years. I invoice every client, every 4 weeks, no matter what (setting a reminder in the task table is really helpful when you have multiple projects running).

Sharing Inspiration Images with Clients or Team

Embed images from site visits

When entering the task on the table, you can use tags to assign it to a project, a person, or anything you choose. Then, on the project page, you can copy this table and filter the view to show only those tasks related to the project, or a team member, or any other tag you’ve set up. The tables are called ‘databases’ and are the key to unlocking the true power of Notion. If you’re running a team, each member can utilize a custom dashboard showing only their projects, tasks and deadlines.

This summer I’ve had an intern working in the studio and I build out the weekly task list each Sunday for the week ahead so it’s clearly laid out for them when they arrive on Monday. I can include links to SOPs and all the project files and information they need in one place. This saves both us time and limits questions (“Check your Notion dashboard”).

Task Table

Filtered Task Table for a Team Member

Any project specific commitments can be embedded directly in the weekly schedule by pasting a link to the project page or, even links to specific blocks from any page. In the schedule above you can see I made a site visit on Wednesday afternoon and the To-Do list for that project is hyperlinked right in the schedule. Clicking on it brings me to the project dashboard and the in-progress items for each stakeholder are immediately visible. Each toggle by the stakeholder can be clicked open revealing the outstanding items, documents and anything related right there.

Below that is a task table with a filtered view of the tasks related only to this project.

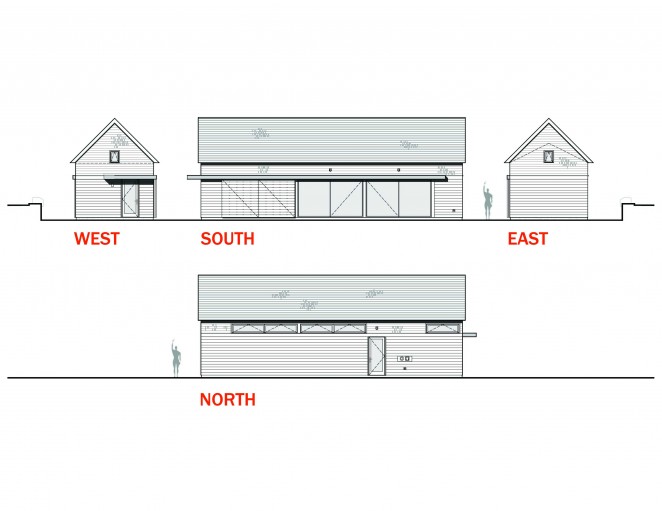

Project Dashboards

Dashboards are simply a collection of the various building blocks available to you in Notion: text, images, hyperlinks, images, videos, tables, quotes…the list is long. I create one for each project, and once you have a format you like you can turn it into a template to use for all projects (download my template to see the one I use).

When starting a new project this template brings over all your office standards in one click. My project template has an embedded a project brief, meeting notes templates, site visit templates, design and documentation checklists, code and site analysis information, client and contractor onboarding information, links to questionnaires, task tables, and more.

Don’t let this overwhelm you, all of this can be built out, customized and added to over time to suit your needs.

Creating custom dashboards for clients with all the project information you want to share - current drawings, checklists for next actions, contracts, permits, invoice due dates, and project wikis - empowers you and your clients/collaborators to seek out the information they need rather than picking up the phone, emailing, or worse - texting you - to ask! Simply share the project dashboard and teach them to check there for updates.

Project Specific Task Table

Checklist Example

As design professionals, our work involves handling an abundance of information. From site and field documentation, to client and contractor requests for changes, to design ideas and inspirations; all of the administrative tasks of project management can easily crowd out the exciting work that drew us to this profession, which for most of us is design.

I've found that Notion has provided a framework that's easy to keep updated with to-do checklists, preconfigured systems, a place to collaborate with clients, consultants and contractors, and a place for me to collect and organize all of the administrative minutiae in one place. No more stickies lining my monitor's perimeter, or bookmarked links in random folders; when it's project-related, I have a place to paste it and keep track of it.

Download my template and watch the videos above for more details on how it can help organize your professional practice.

Still not convinced?

A few more Reasons I use notion

In the past I’ve used Trello, Asana and Evernote to run and organize my business operations. While Evernote was searchable, it was messy. Trello and Asana were as customizable as I had wanted. And implementing templates and systems with each was hit or miss. These are some of the strengths of Notion and considerations when choosing a new tool:

Easy to use + implement

Onboarding with Notion is simple; a very low learning curve. Advanced features unlock more potential, but take longer to comprehend and integrate. It can grow with your needs.

Systems Oriented

Templated work will save you time managing your projects + administrative tasks. Notion allows you to create custom templates for almost anything you can imagine: projects, notes, files, tables, etc.

Collaborative

Sharing Projects + Pages with clients and collaborators is easy and allows everyone to see the most up-to-date files, checklists and information. You can assign tasks and comments to others by right-clicking on any object, assigning a due date and custom requests.

Searchable

Notion allows you to find the information you’re looking for quickly and reliably, listing every instance of your search phrase while typing. Evernote used to be amazing at search but the more I loaded it up, the less functional it became.

Customizable

Collating various media is important for our work as designers: images for reports + inspiration, video embeds, hyperlinks, product ideas + references, notes, checklists, tables…Notion has them all. Simply click the + to add. Dragging blocks around is intuitive so you can create the structure that suits your needs.

Graphically Pleasing

With a minimal interface, Notion can be what you want. Add images, banners, colors, etc. Out of the box, it just looks good and if I’m sharing this with clients I want it to be representative of my brand.

![Smoked Whitefish, Christmas Eve 2018 [ Photo: Eric Reinholdt, 6DMKII 100MM f2.8L ]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58b58a96f5e231aa75f48ec4/1548074005888-VGANK4WAKRD6IRHU8F3Z/whitefish-dad-2018-2.jpg)