As this project enters its twenty seventh month in construction (!) the crew have begun finishing the interiors. The supply chain delays of the pandemic, a prolonged labor shortage, unlucky and unfortunate delays have made for an epic build.

I’m working with the most patient clients in the universe it turns out.

February is roughly mid-winter in Maine and a good time to turn attention inside!

Not all architects consider interior design as part of their scope of work, but for a residential architect it’s at least half - and an essential part - of what I do. I want a singular holistic vision and a reflection of the architectural design solution applied consistently throughout. There are, of course, varying degrees of influence we can exert. I’m hardly a Frank Lloyd Wright fan, but I always admired his ability to design every last detail in his clients’ homes. From window glazing to tableware, linens, art, and accessories. He designed every piece of furniture and, fixed their positions, to curate the overall experience, both inside and out. Although most people have limited budgets and patience for this degree of design integration (especially after 27 months in construction), for architects it remains an aspiration.

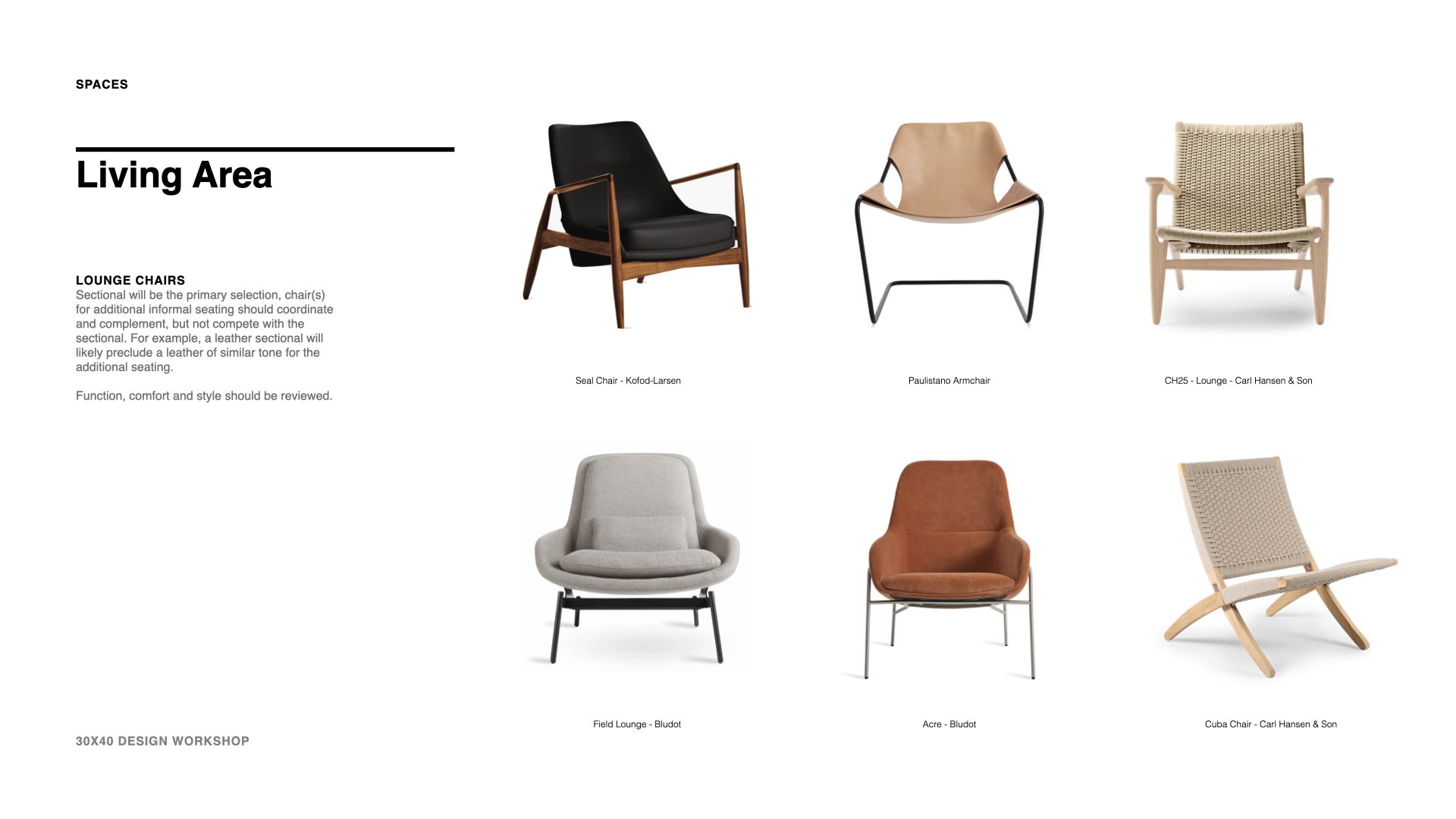

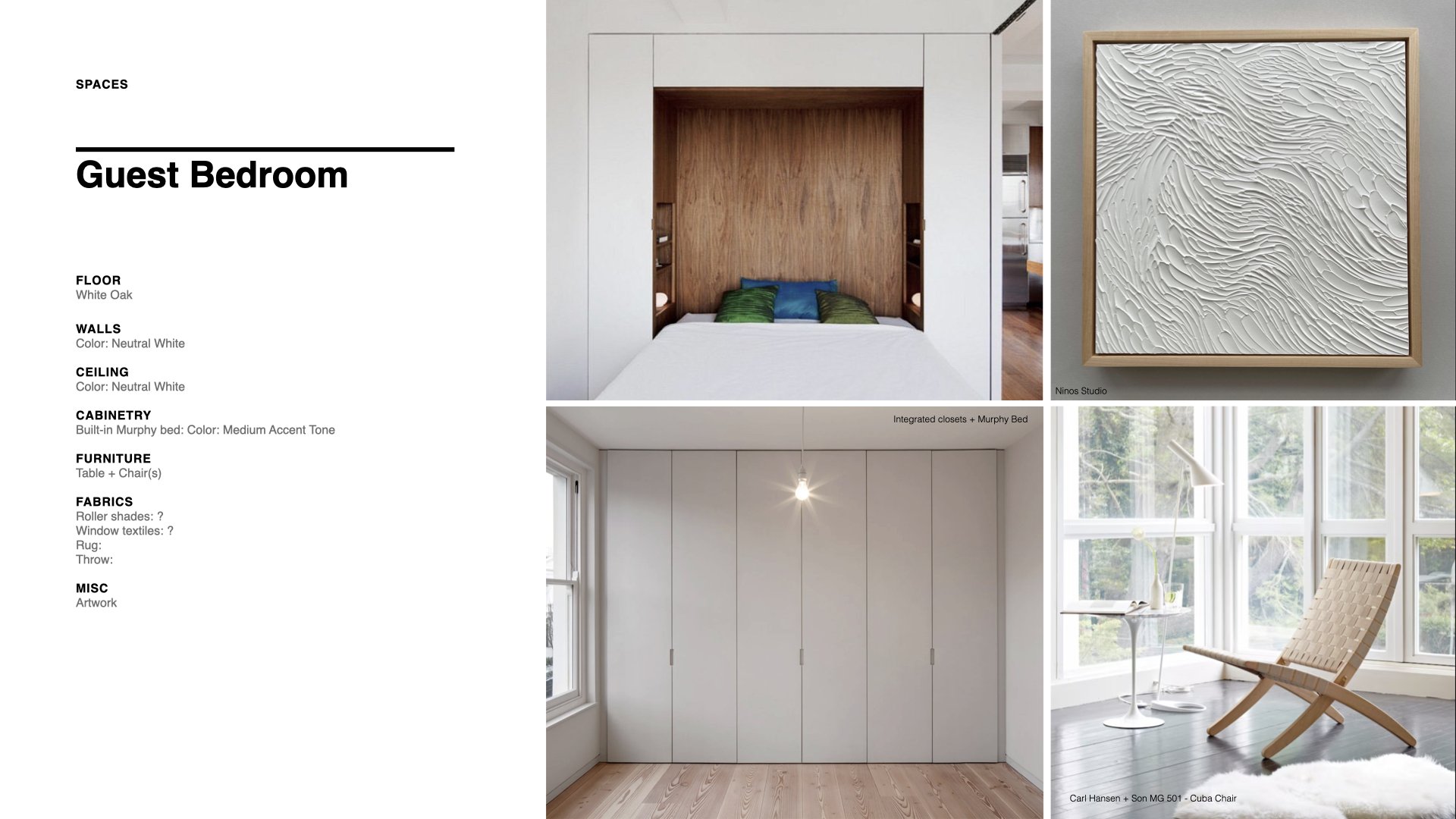

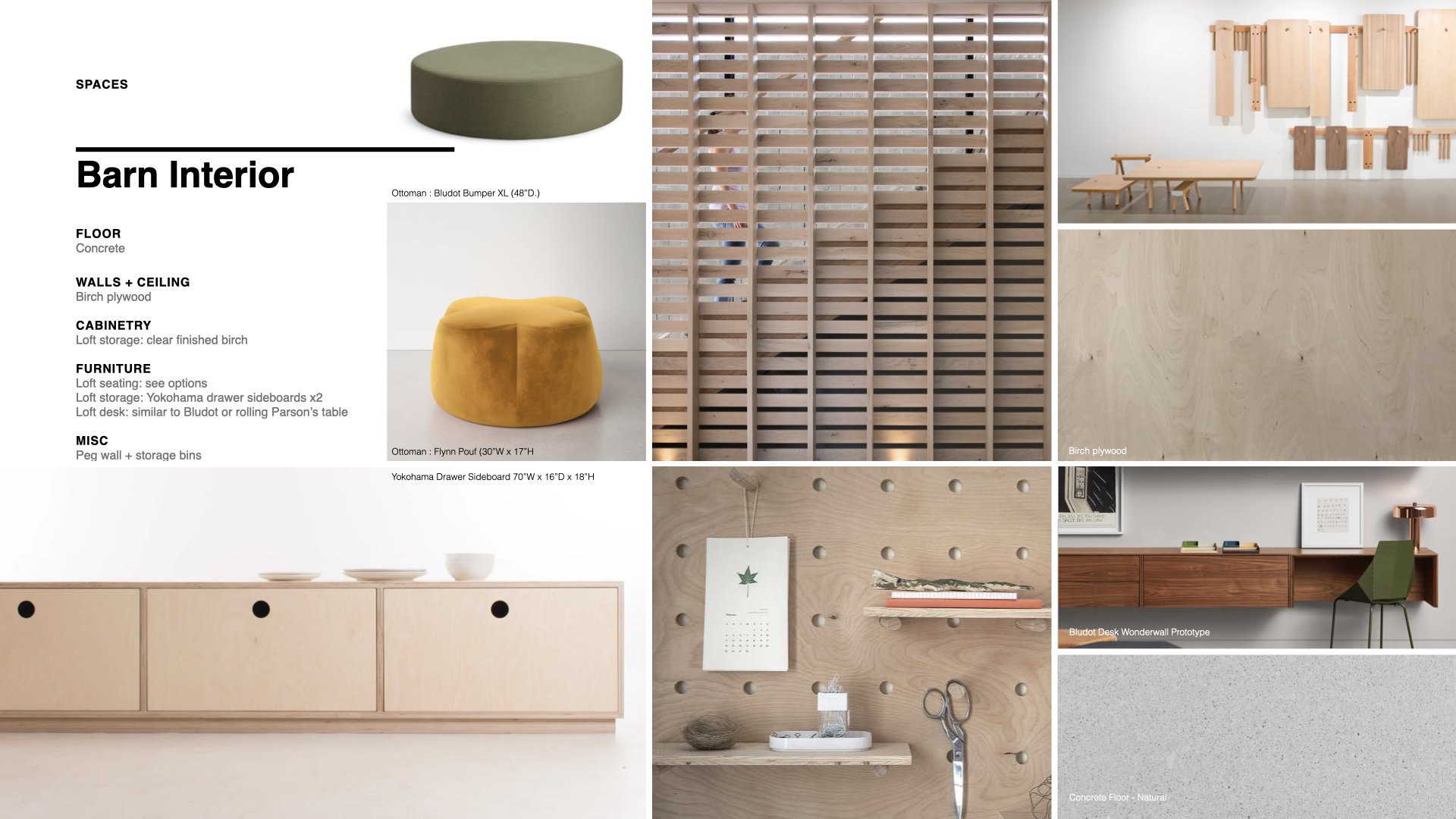

My interior design process is a combination of design and curation. Some elements, such as door and window details, cabinetry, hardware selection, plumbing, and lighting fixtures, need to be designed and integrated, while others, such as furniture, accessories, and textiles, can be left for curation.

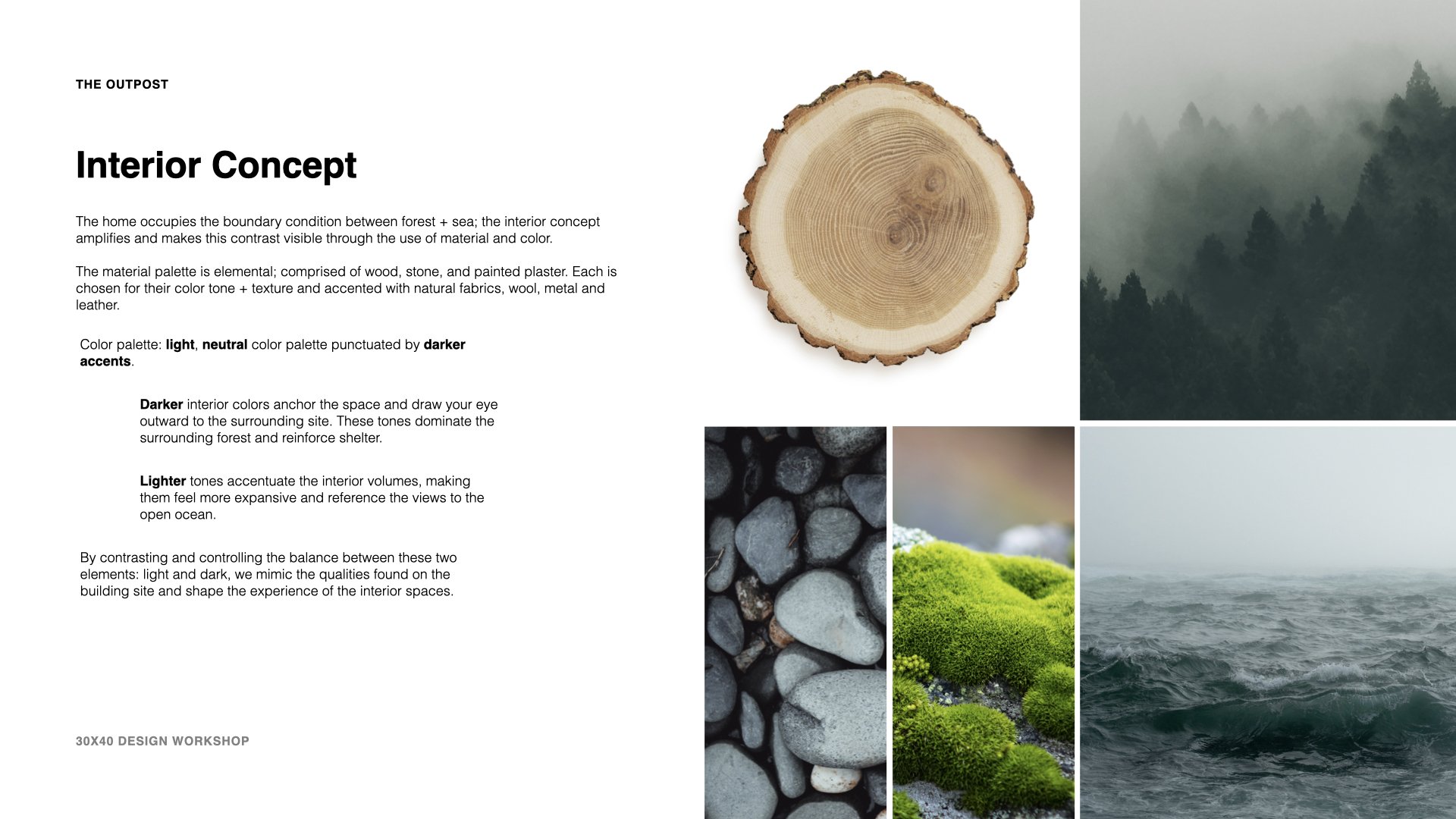

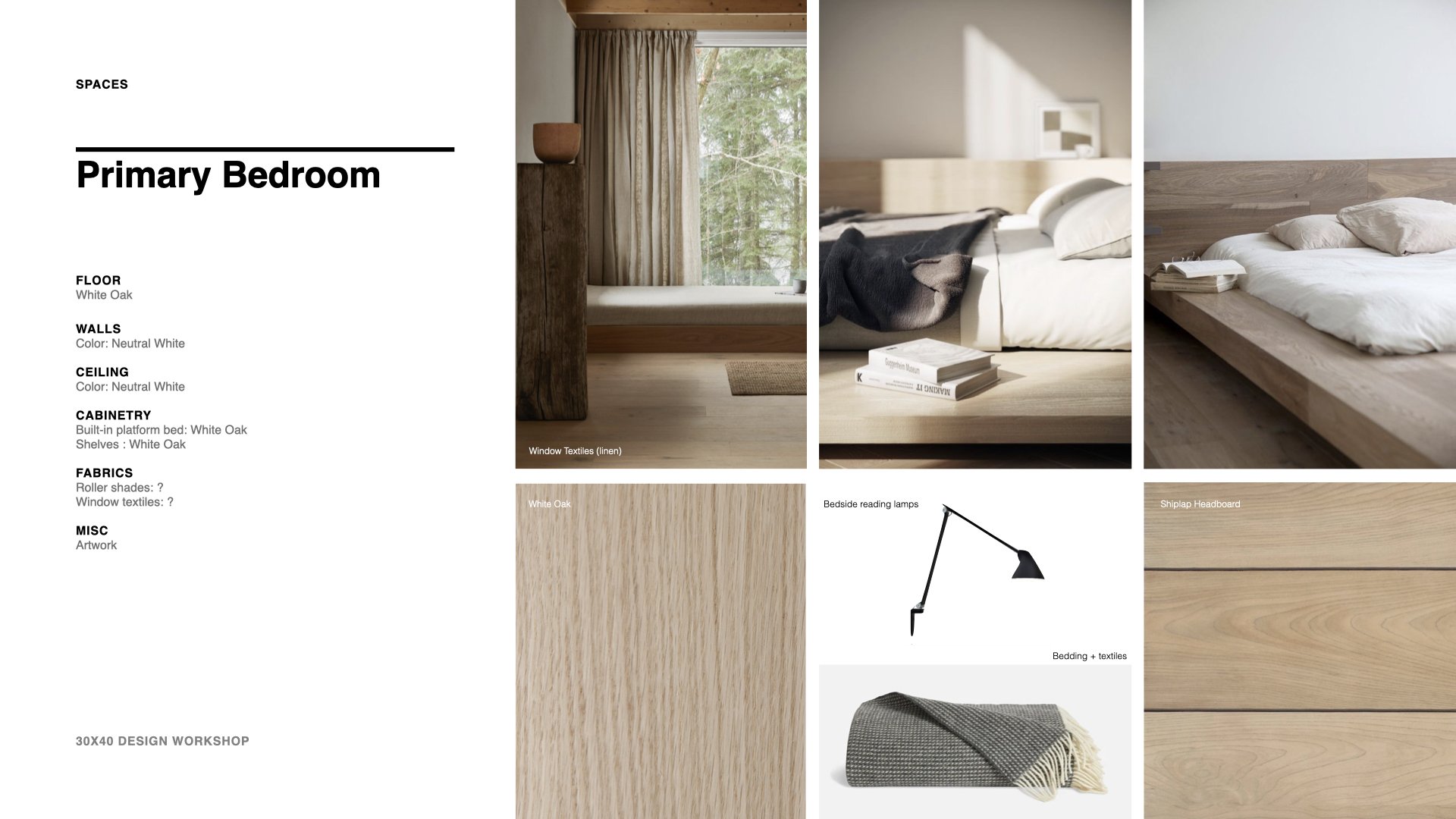

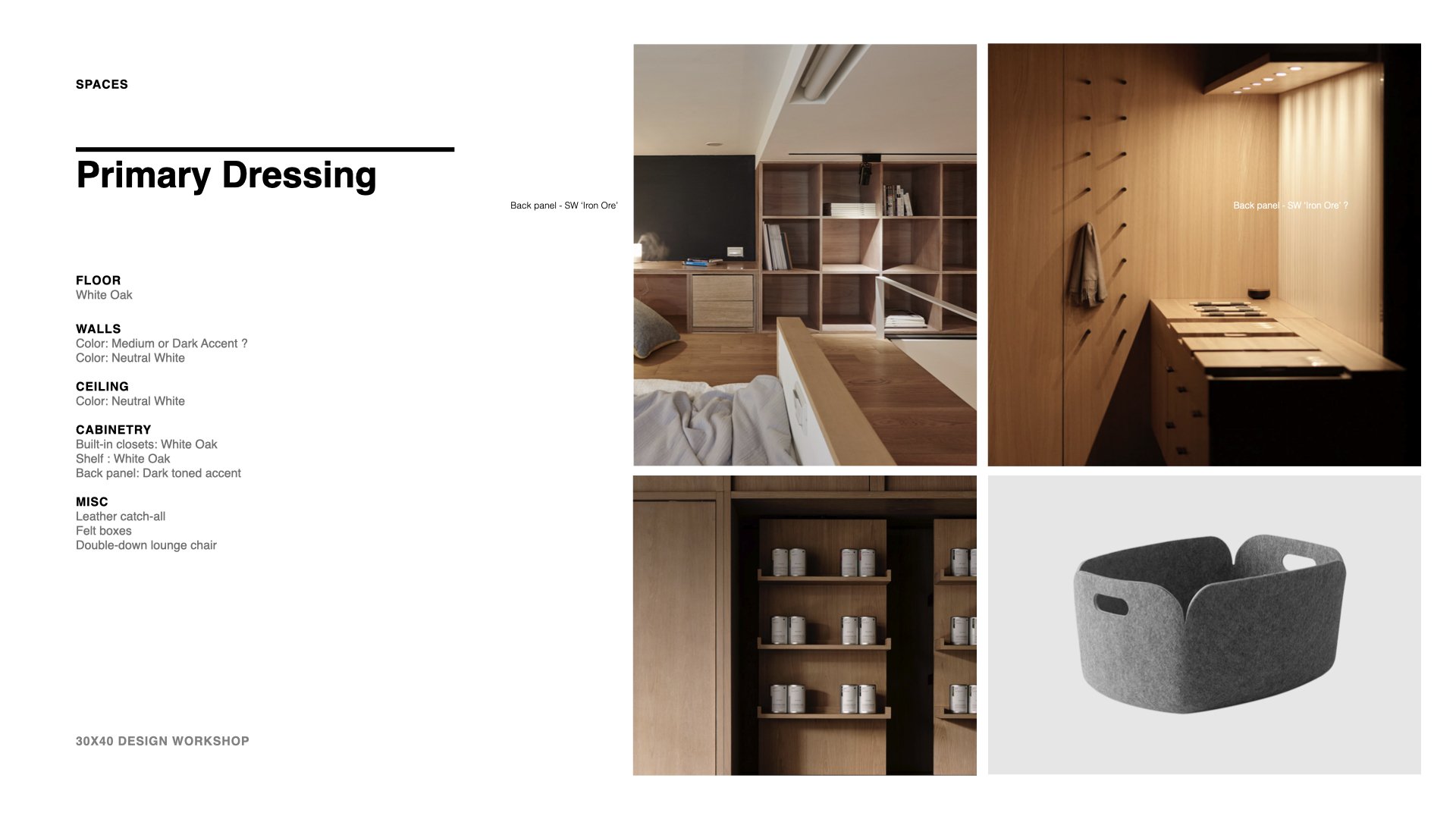

In the video I share my interior design process and the story (mood) boards I create for my clients. It starts with a concept and ends with a detailed focus on each space. The concept here is drawn from the colors, textures, and light patterns in the natural surroundings. You’ll see how materials, texture and color combine with the architecture to mimic the unique boundary condition this home occupies between forest and sea.

Designing a home involves many decisions, from furniture and color choices to lighting and accessories. Every aspect contributes to the overall look, feel, and function of the space. Without a concept guiding our decisions, it’s easy to simply collage and combine images we like of disparate ideas. The sum total can feel disjointed.

A concept provides:

Cohesiveness: A strong concept ensures that all elements of the design work together in a harmonious and cohesive manner.

Clarity: A concept provides direction and helps define the overall aesthetic and style of the space, which can be especially helpful when making design decisions.

Functionality: A concept can help dictate the functional aspects of the space, such as furniture arrangements, lighting, and storage solutions.

Emotion: A concept can evoke emotions and create a desired atmosphere or mood in the space, making it a personalized and meaningful environment.

Impact: A well-designed concept can make a lasting impression and create a memorable experience for those who use and interact with the space.

Architectural Material Palette

Most people lack the ability to articulate precisely what they want in a space and Pinterest can unify our vision. My clients and I use Pinterest to collaborate and establish a common design language once a concept is agreed upon rather than to define the design vision or stylistic overlay. We don’t linger there though, I prefer to further cull the images and develop a story board presentation (see images below). We want to create our own unique work, derived of our own ideas not simply a collage of rooms taken from dozens of other spaces. I find using story boards in the process helps my clients see the home as their own unique design.

It’s our job as interior designers and architects to make visible the invisible, latent forces in a place. This home is sited on an island, six miles out to sea and there the weather, the changing light, the seasons; everything is about contrast. The home sits on the boundary between two very different environments, the forest and the sea and it controls one’s experience of each. I want the interiors to be the canvas that makes this contrast visible.

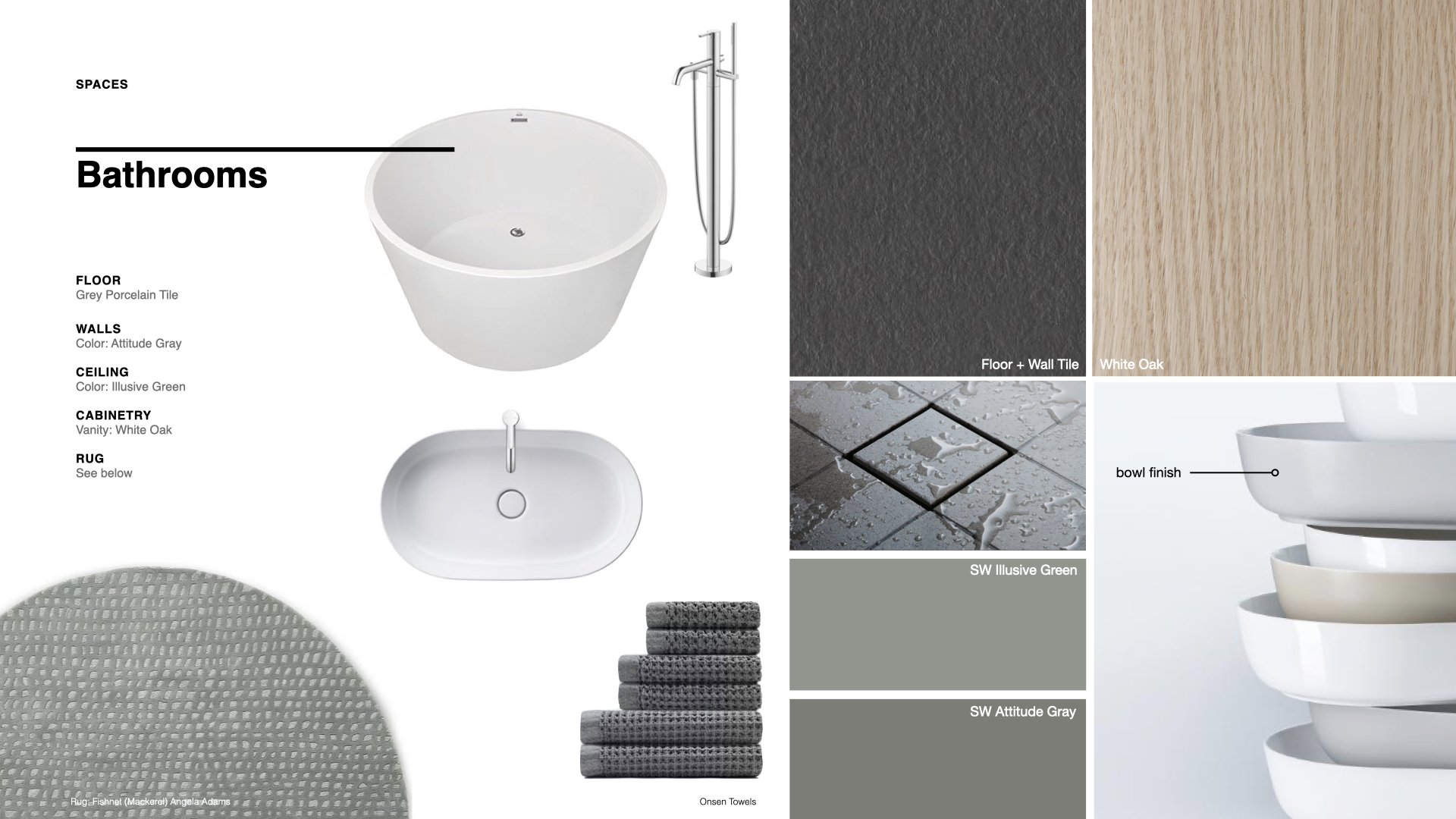

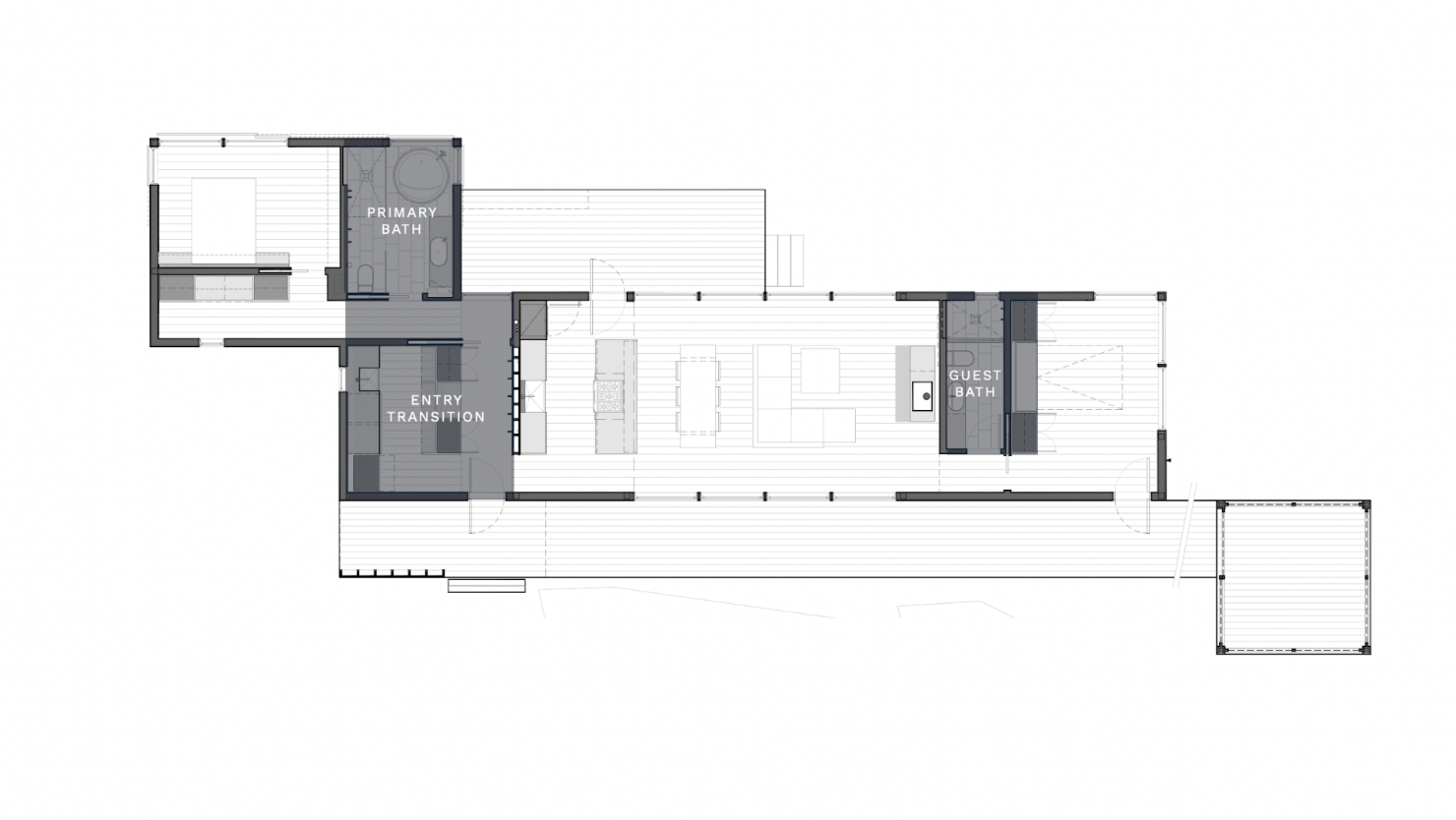

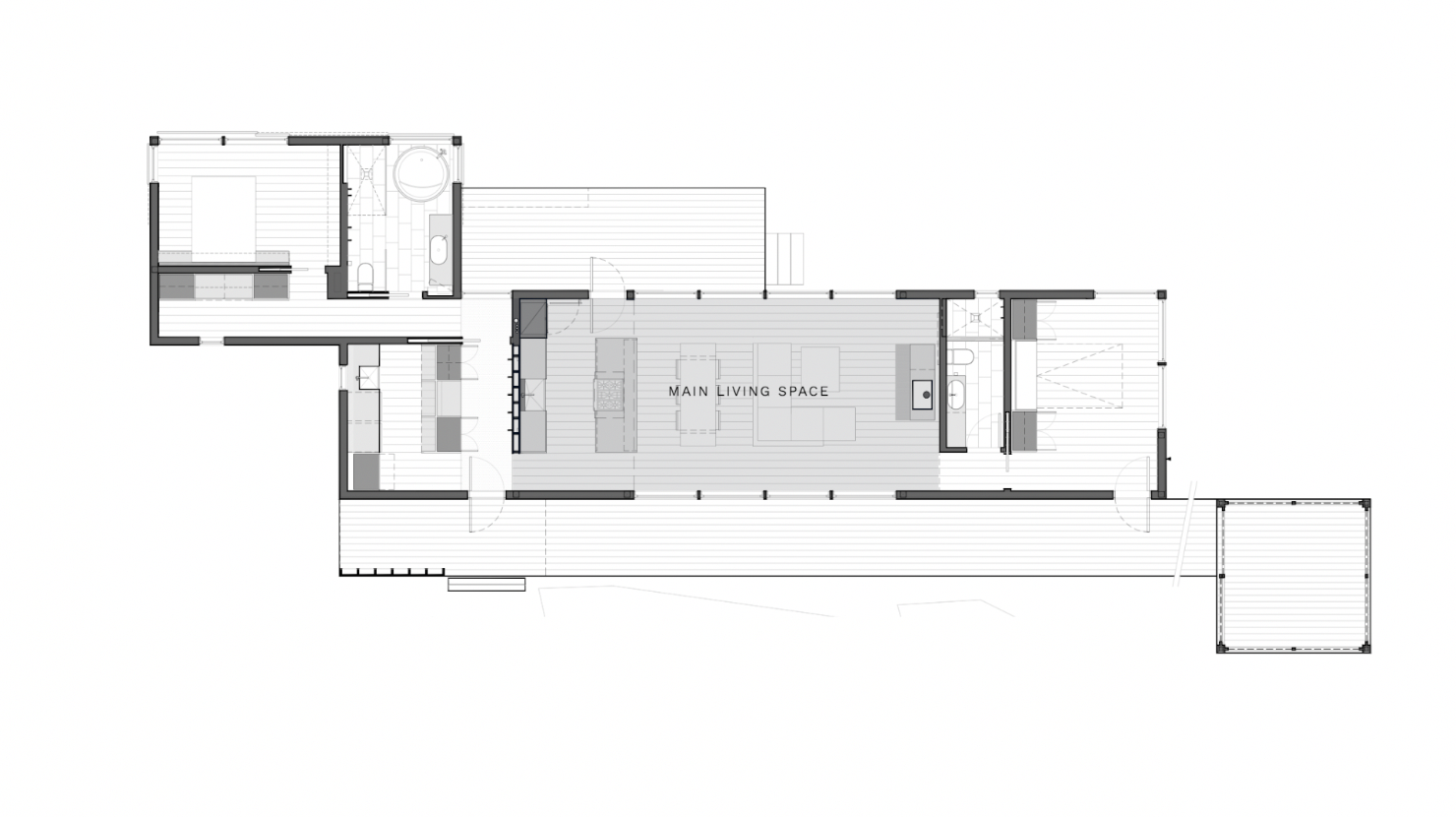

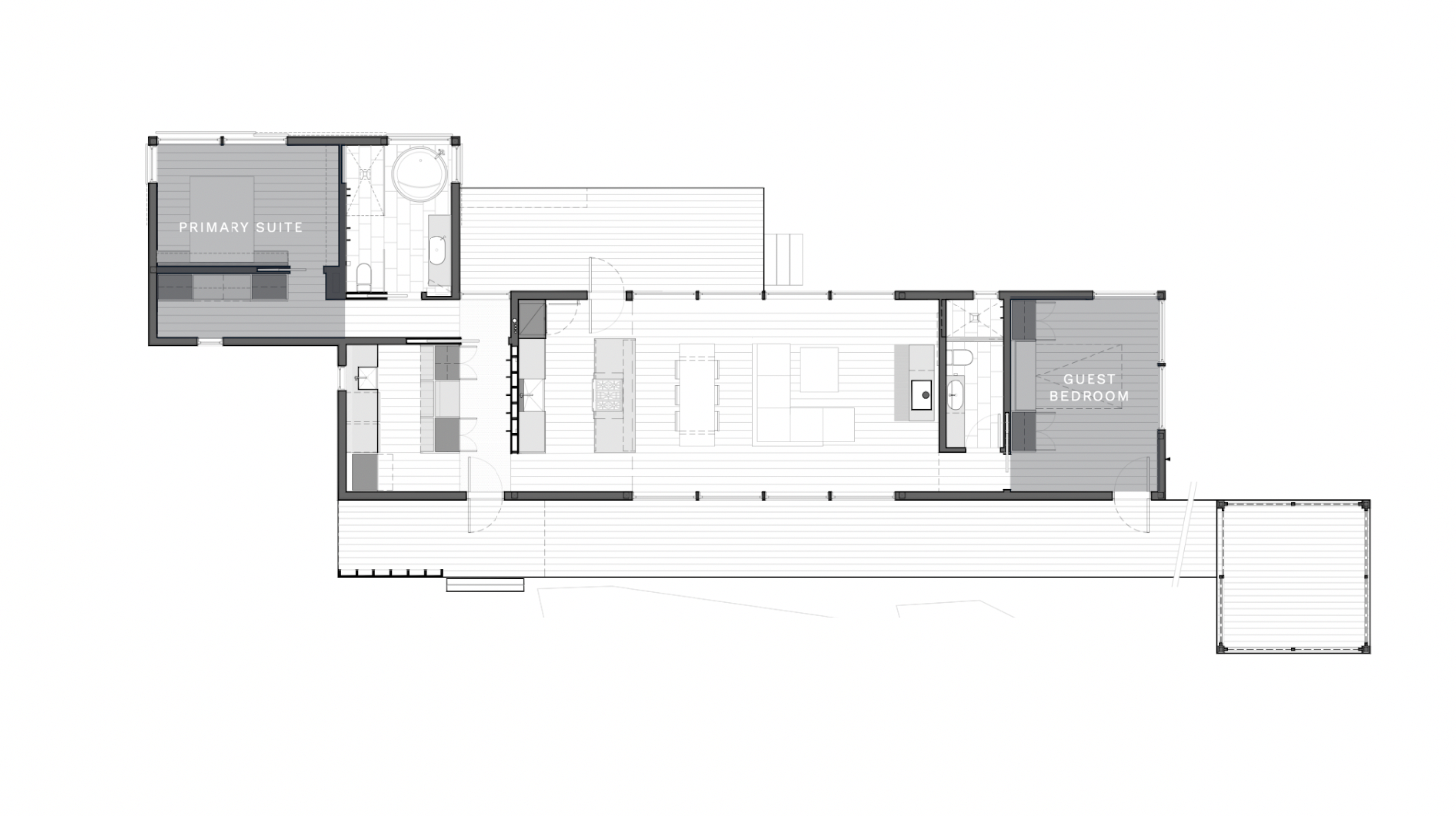

As we look at the floor plan there are natural places that might be more like the forest, more sheltering, darker, and lower in scale. The obvious places are the entry area, and the bathing spaces. And then there are the main living spaces which are larger, brighter with taller ceilings and sweeping views. In the bedroom and supporting spaces we can alter the balance between light and dark, mixing the two.

Material Palette Flat Lay

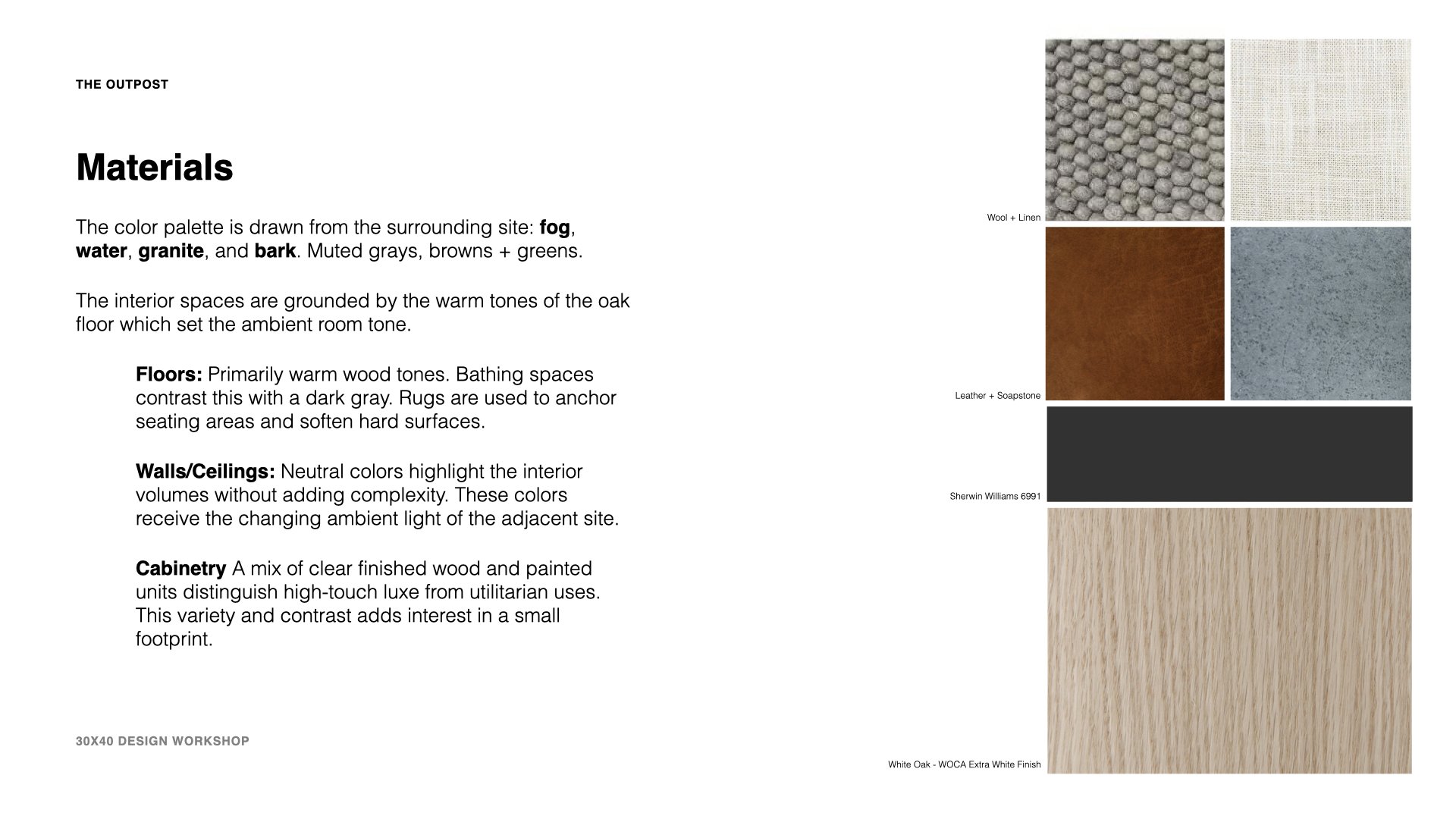

Materials

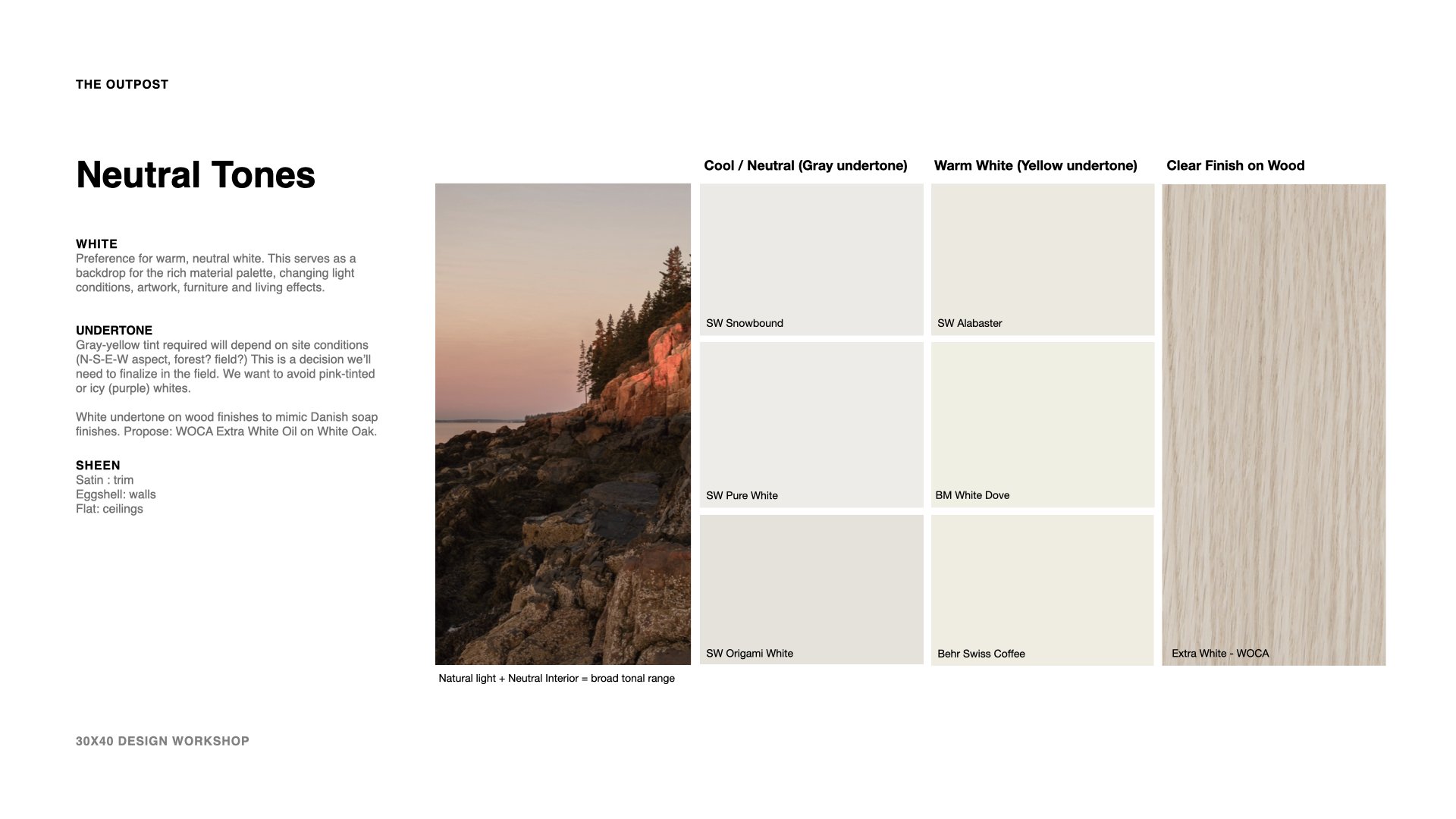

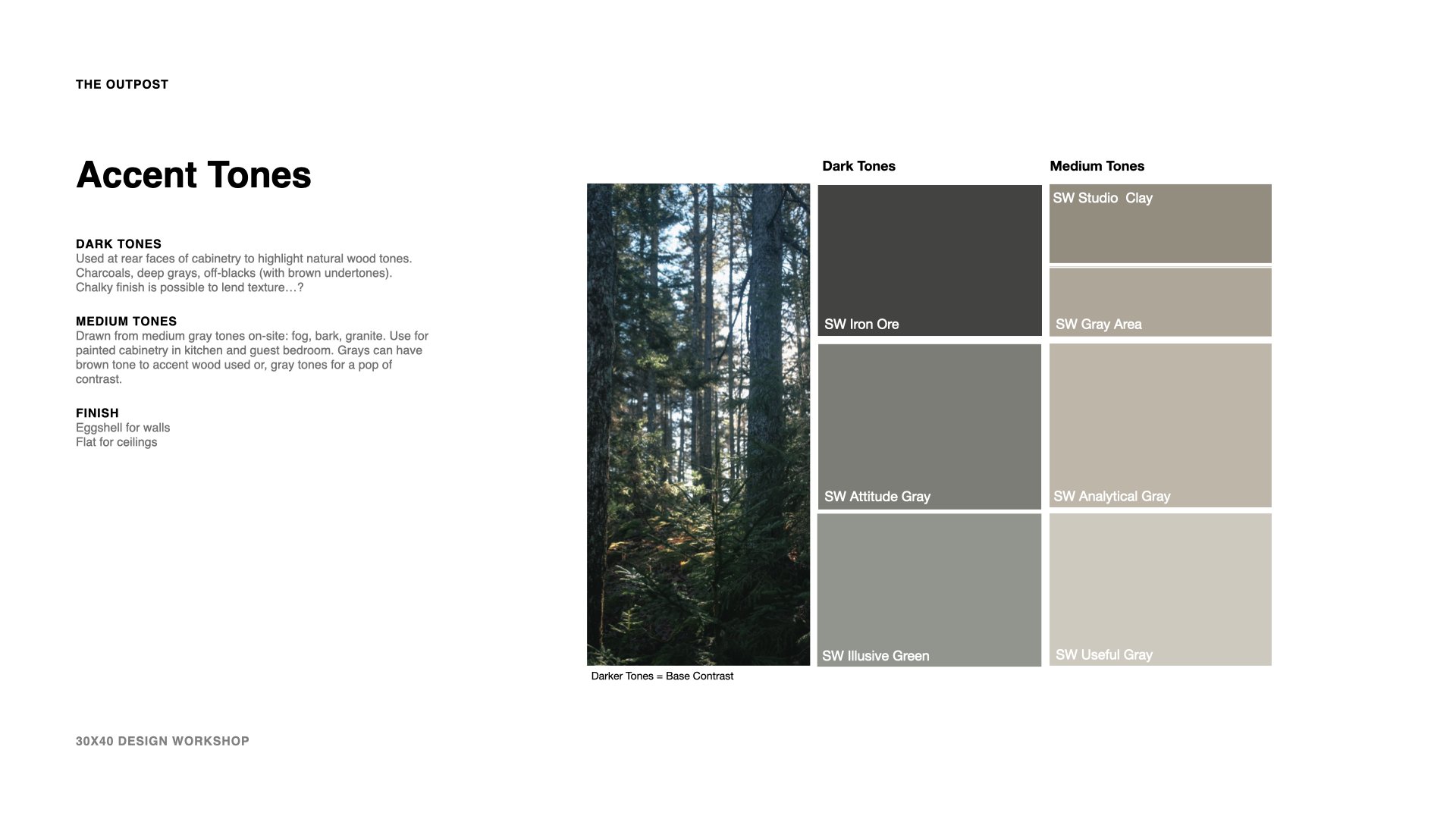

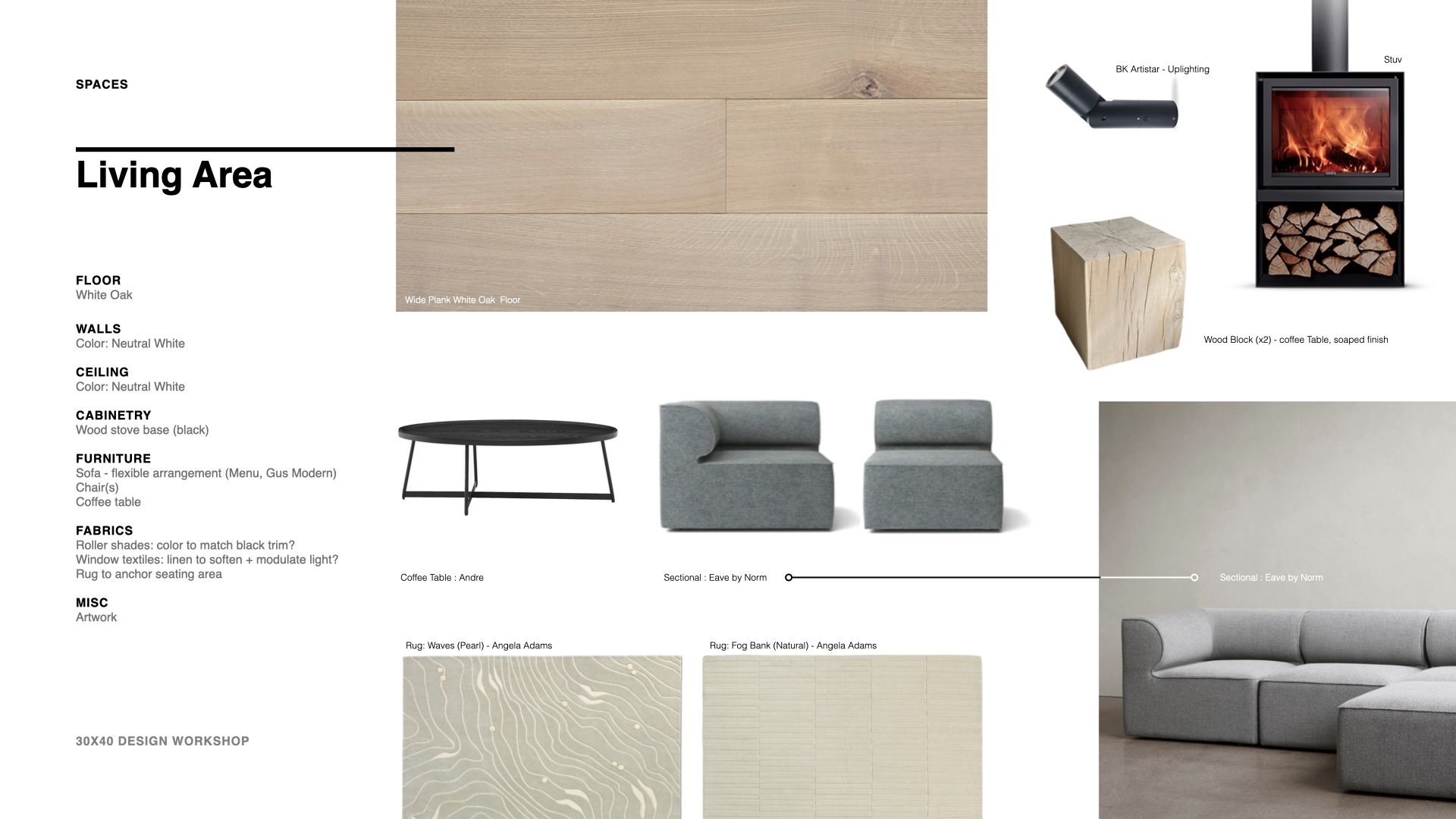

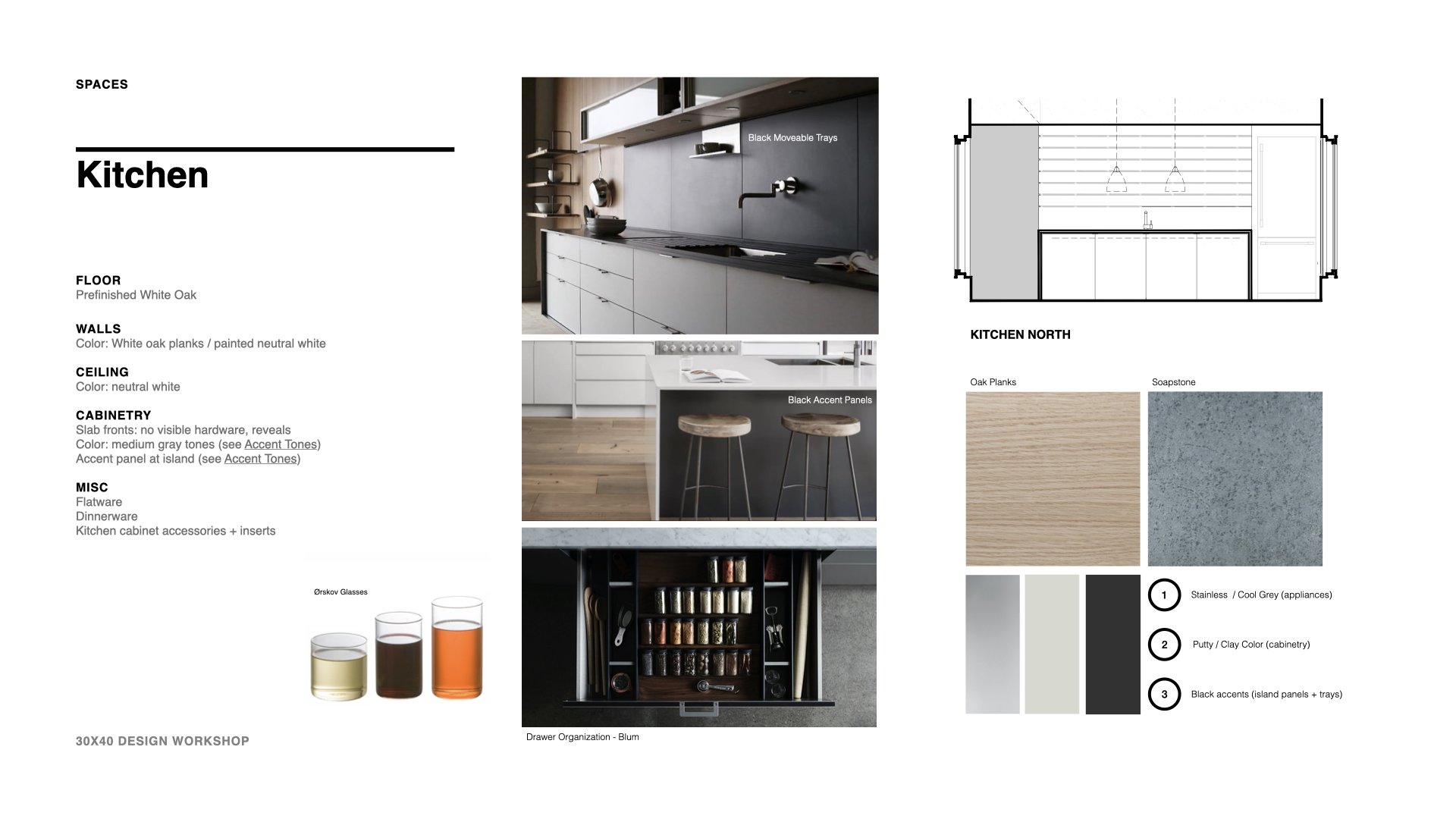

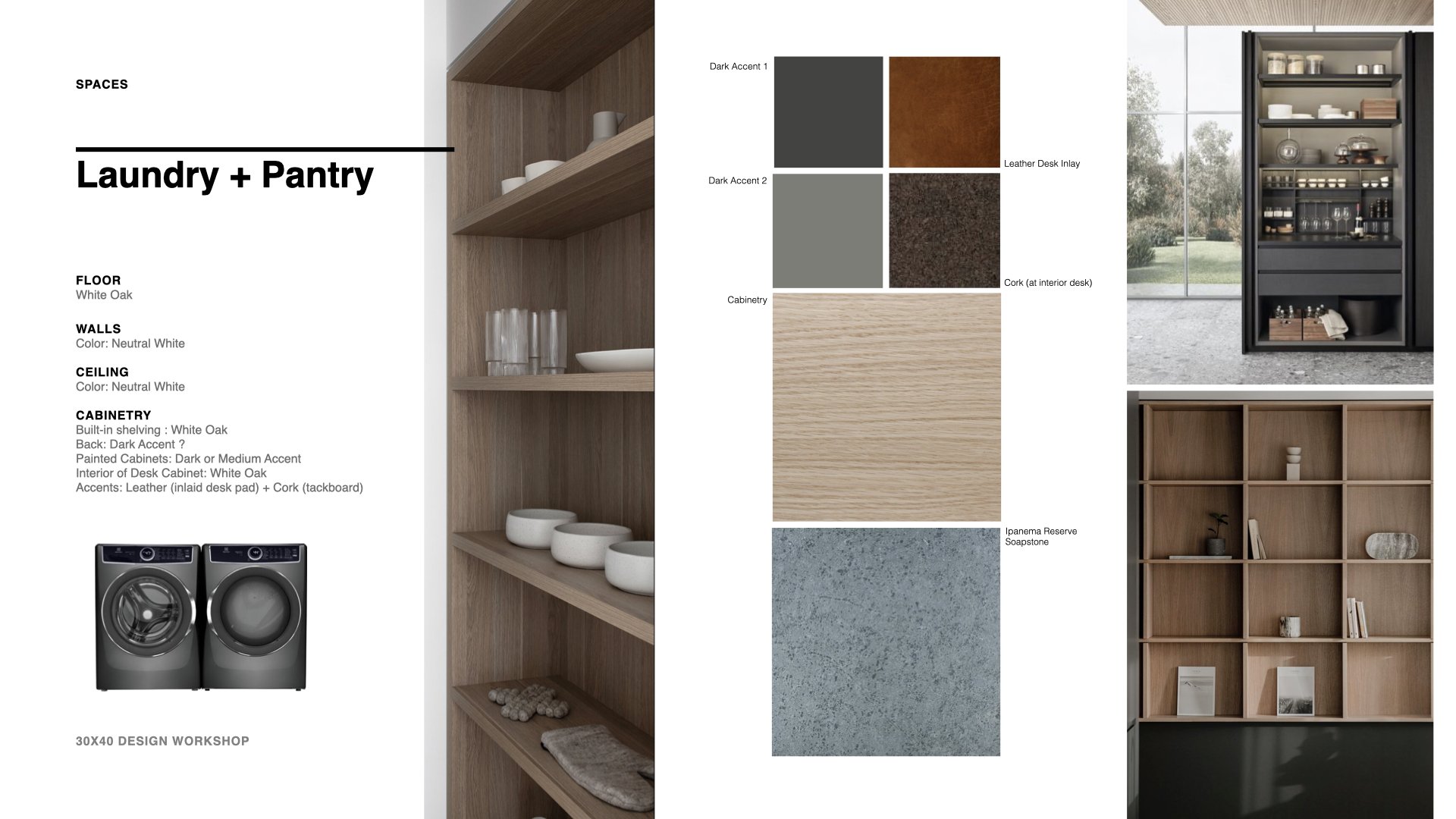

Contast as a concept is versatile and can operate on many levels: tonal (light and dark), textural (smooth and rough), emotional (refined and casual, high/low) and so on. Given this is a small home, we want to limit the material palette so, I’m proposing to use natural wood, painted plaster, and stone as the primary materials. I’ll be accenting these with metal, leather and some fabrics.

Be sure to watch the video for more details on the material selections. Here’s the palette I’ve chosen:

Floors

Wood: 8” prefinished (solid) White Oak, Carlisle Wide Plank Flooring

Porcelain Tile: Mosa, cleft face

Other: 5/8” Coir matting

Walls/Ceilings

Snowbound, Sherwin Williams

Illusive Green, Sherwin Williams

Attitude Gray, Sherwin Williams

Iron Ore, Sherwin Williams

Cabinetry

Stamped Concrete, Sherwin Williams

Argos, Sherwin Williams

QS White Oak, WOCA Extra White Oil

Counters

Ipanema Reserve Soapstone

Below is an excerpt from the working presentation I reviewed with my clients. Download the presentation template here.