In this video I review seven of the most common tricks I use as an architect to separate space in an open floor plan. I talk about the advantages and disadvantages of each including: the room within a room concept, open shelving, thin wall planes, thick wall masses, sliding walls, fabrics (metal and cloth), and hybrid systems.

Choosing Pocket Door Hardware - Pro Tips

In this video I discuss the secret to pocket doors' success - selecting the proper hardware. I discuss quality architectural hardware specifics from manufacturers like: Hafele, FSB, MWE, Halliday & Ballie, Sugatsune, Accurate and others. I review the optimal track configurations, flush pull handle sizing and shape considerations, and the all important lockable pocket door function.

Embracing the Narrow Home

The simplicity, directness and beauty of a narrow floor plan makes it suitable for many building sites, not only those on tight lots. In the video I discuss in detail twelve compelling reasons to embrace a narrow home design. If I've convinced you; be sure to check out my offering of efficiently designed, affordable, narrow home designs in the shop.

Advantages:

- Light

- Warmth

- Ventilation

- Efficiency

- Flexibility

- Expandability

- Vertical Separation

- Horizontal Separation

- Cost Savings

- Sense of Exploration

- Borrowed Space

- Diversity

An Architectural Recipe...of sorts...

I received a box of concrete samples from Get Real Surfaces recently. Small, 3"x3" squares of varying finishes and color mixes. Perfectly sized to fit in your hand, for sharing with a client in a meeting, or for toting around to the job site to imagine them in a finished space. The samples themselves are beautifully rendered objects in their own right. For an architect, materials are the cooking equivalent of ingredients. Just as a chef enters the pantry to select ingredients for an entree, the architect consults their sample library. For me, this happens throughout the design process. In the very beginning a material concept informs the building concept. As we move deeper into the design that concept is shaped by the building layout, the client and the site. Together it evolves.

Stone, concrete, wood, tile, glass, metal - the raw materials of building can be chosen for their reference to particular place, one's taste or just because of their beauty. But I have favorites and they're a narrow few.

Here's why.

The paradox of choice is such that having more options doesn't actually yield more freedom to choose; rather it makes it even more difficult to feel like any selection you might make is 'correct'. Having a few favorites means the project quickly can focus on the features inherent to the design - its form, light and the environment all of which the material selection can highlight and not simply on using the most fashionable faux pebble tile.

The Japanese Pritzker prize winning architect, Tadao Ando's work offers a rather extreme take of this position. His material of choice is reinforced concrete and he uses it everywhere, in every project. It's weighty, but there are moments of extreme lightness too in the scale of the volumes. The gray of concrete is a canvas upon which light softly renders form and space. The earth and weather develop a patina on the concrete that helps to fold it into the site, it's rugged and supple at once. I admire the stillness of his work and his ability to achieve such depth of emotion from a singular material. Less, in fact, is more.

Focused choice in material selection allows this kind of a simple dialogue to take place. It allows the place and the building a voice. Solid and void. Weight and weightless. Dark and light. Warm and cool.

I love concrete as a building material deeply. Not only for its color and its tone, for its feel and its weight; but also because it's expressive of the process by which it was created. The form-work permanently reveals the skill of the craftsman who built it and the subtle markings of the ties and the aggregates that comprise its mass.

For me, concrete also needs the warm counterpoint of wood. The informality of Douglas fir, the ruggedness of Red Oak, the refinement of Maple, the tailored appearance of Mahogany, the evenness of White Oak. Each of these pairs beautifully with concrete and elicits different emotions. Like concrete, wood can be subtly effected by the way it's finished or cut: plain sawn, rift-sawn, or quartersawn; each reveals a different graining pattern and tonal character. Subtle but wholly beautiful.

These are effects that are heightened and only appreciated when there's little other noise to drown them out. Just as the tenderloin requires salt, concrete requires wood. Nothing more.

...except perhaps a side of glass?

Design Inspiration

For me, the beginning of a new design project brings with it, in equal measure, both excitement and fear. Fear because the quest for design inspiration is an unknown path. The idea may arrive in an hour, a day, a month or, the deep nerve of fear: never. The architect Maya Lin, perhaps best known for her Vietnam War Memorial, likened her design process -- the discovery and inspiration -- to that of laying an egg. Her egg is an idea that arrives "fully formed" and it's the result of an unknowable amount of thought, study, sculpting , sketching and writing.

I'll admit to some envy of her process. Mostly because it results in a completely fleshed out idea, ready to develop into a coherent, beautifully articulated project. I console myself with the thought that she suffers the same anxieties all designers face.

I find my own search for design inspiration as elusive today as it was when I entered architecture school in 1991. It's an unpredictable muse. What I know now, that I didn't know then is that my ideas only come as a result of sketching. Much like writing, the ideas flow from the act of putting pen (or key) to paper (or pixel). The process of sketching is one that is taught early on in school as a means of thinking. It's a way to arrive at the genesis idea that sets a project in motion. Architects call this idea a ‘parti’. From the French, Prendre parti meaning "to make a decision".

And for an architect, nothing can replicate that moment when that idea arrives.

The Problem

I use sketching to document and synthesize thoughts about the site, surrounding buildings, the client, the necessary spaces, the climate, zoning restrictions, budget - basically all of the situational factors that represent the context of the architecture. While that seems like a lot to absorb, there are always certain themes that demand more attention than others. This makes the process easier for me as I dig deeper, a natural hierarchy begins to establish itself. There are building codes, restrictions, design review boards, wetland's commissions, budget, client proclivities - these are constraints that every project confronts. The goal is to understand all of the rules for the project and then set about creatively following them. It's often these constraints that can be the genesis for an exciting work of architecture.

A new project I've been working on is an interesting case-study for how this process works.

The client brief was to replace an existing, one-story dilapidated structure and double the leasable space of the property with retail on the ground floor and a restaurant on the upper level and an apartment on the uppermost level. The small 20-foot by 80-foot lot meant that the additional square footage would require a multi-story solution. Because it's in a business district it shares a property line with a neighboring structure to one side and to the other it looks out on a parking area and an unappealing, cluttered rooftop.

Seems straightforward, right? The building next door has windows along the entire shared property line and some of them serve bedrooms. So, legally we can't build right up against the property line and obstruct the bedroom windows. Given that the lot is only 20-feet wide, sacrificing any square footage would limit the leasable area and the monthly ROI for my client. The lot is also in a downtown business district with a Design Review Board which requires buildings to fit with the established character of the neighborhood, which is, buildings constructed to the lot lines. Add to this, the fact that the lot is oriented along a north-south line means collecting southern light for an upper story restaurant will be tough. It's a tricky problem, but there's one thing that stands out above all else when I think about how I'll organize the structure, that's where I begin to focus my efforts and my search for inspiration.

The Idea

Knowing that I had to preserve the exit pathway for the upper story windows of the neighboring structure reminded me of the complex network of foot paths that predominate the walkable European city. There, alleys were usually remnants of old pedestrian streets. And, while these pathways have become ever smaller as the cities became more dense and the land more valuable, the alley has persisted because they're essential for service, access, light, and air.

It was this realization, that I could create an alley between the two structures that was the spark that led me to the organizational design solution. But, this had to be more than just an alley. To maximize its functional potential on the small lot it had to provide the circulation for both my client's building and for the neighboring structure's exit windows, entry, exit, light, air - all of the things that an alley provides we can make use of. I won't get into the legal and code implications of actually constructing an alley between buildings, as it's complicated and somewhat uninteresting - let's just say it's a good solution to a complex problem.

The alley idea is a simple organizational concept, that helps me to begin laying out the building spaces on the site. But there are other ideas that I began to explore too and those informed how the building might consciously work to affect the environment around it.

In Part II, we'll discuss the visual inspiration and see the building take shape.

The One Space You Can't Live Without

I'm convinced I was born in the wrong part of the world. Have you ever had this feeling? I love my family, don't get me wrong, it's got nothing to do with them. My parents moved from my birthplace on central Long Island in New York a few hours north - upstate - to a small town baseball fans know well, Cooperstown. It was baseball that connected the economy to the outside world drawing thousands of tourists to see heroic players inducted into its hall each August. It was farm country and when it wasn't farm country, it was snow country.

I never played baseball, and the smell of manure made me long for the trade winds of the tropics, and the searing heat of the desert, the salt air of Big Sur, and a lush, green Kyoto.

Not coincidentally, all places more temperate than upstate New York and also places where it's possible to live somewhere between inside and outside. Not fully one or the other. Something I never had a chance to do.

I'm fascinated by open air living as a human first and of course professionally as an architect. It certainly isn't a recent invention, but it's one that has been co-opted by modern architects as an instrument to connect people more fully to their surrounding environment. As a modern architect myself, now practicing in the northerly, marine climate of Maine, I can't help but drool over the imagery and apparent freedom of my colleagues practicing in more temperate climes. No need for screen doors, or tightly controlled waterproof building shells their architecture flows from inside to outside unobstructed. These structures define places for being, for living - without constraints or boundaries.

But I know as an architect too, that even though we may have black flies and mosquitos and snow - which flies for more of the year than we'd like - we still have a need for transition spaces in our architecture. Open air living isn't completely possible but these transitions can afford the suggestion and on rare days even deliver on the promise.

I would argue that transition space is the one space no work of architecture can exist without. No matter where we practice, architects follow similar rules about the need for transitions between enclosed (indoor) and unsheltered and open (outdoor) space. These buffer zones, where we move from one activity to the next are not only extremely useful, utility-driven spaces but they're integral to our comfort and our experience of a place.

Imagine stepping into the the Pantheon's cavernous dome without the large sheltering portico transition. It's not the same. The Greek's and Roman's of antiquity understood this, their architecture is rife with colonnades, porticoes, the agora, the forum - each one had a preamble. Hardly superfluous, they're necessary and comforting architectural devices.

A more contemporary example everyone is familiar with is the porch. Porches give us a place to kick off the mud from our boots, a place to sit outside while it rains or sheltered from the sun and reduce the apparent size of our two or three story homes to something more in tune with the size and shape of our bodies.

We instinctively notice the absence of transition spaces too. Think of almost any tract house in suburbia built in the last 20 years. Are you picturing arriving to a garage door? I know I was. Suburbia has asked that we eliminate the transition space in favor of our car. Step out of your car an into the four walls of your home.

Architects understand the need for transition spaces and leverage their utility. They provide a sense of scale, shelter, enclosure, protection, a sense of arrival and departure and because they lack the strict requirements of conditioned (or heated) space they can be more sculpturally free and expressive.

Modern architecture has surely sought to connect us to our place in a more direct way than its predecessors and transition spaces make this possible as evidenced by these seductive photos of a project in the desert southwest. Almost like nomadic tent structures, the architecture is reaching out to the land, buffering the extreme environment creating pools of shade around the home. This makes the interior environment more comfortable and it provides places to sit out of the intense sun for the inhabitants.

Transition space is the one space you can't live without (there just might be one other one too).

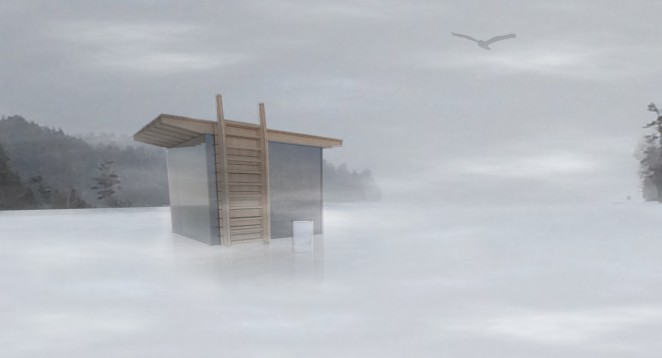

Winter's Exit

The changing of seasons marks the passage of time so plainly. The ever higher, warming sun melts snow during the day, refreezing it each night. Snowbanks retreat from the drive's end. Snow packed hiking trails give way to oozing ice floes. Footprints left in early storms reemerge. Frost-heaved roadways pitch us about on our travels. Roads are posted, "Heavy Loads Limited". The maples give up their sap. Gardens are being planned and seeds started. Nothing escapes the push and pull of this diurnal cycle as we inch closer to the days of summer.

I love this awakening - the transition back to daylight.

Spring also means that the ice huts that dot the hard-water around Mount Desert Island will soon be retreating. I've been watching this particular shack edge closer to shore each day over the past week. That's as sure a sign as any I know - spring is coming. I wasn't born in Maine, so I'm not technically a Mainer, but I've lived here long enough to know what to look for. Watching ice shacks retreat off the lakes is a reliable sign that warmth lies ahead.

These shacks are ad-hoc architecture at its best. Most share the quintessential gabled shape of home, with the occasional, unintentionally modernist, plywood boxes. They're the kind of humble creations that inspires much of my own work here in Maine. Driven by economy and a desire to escape - trading one cabin's fever for another in a cold, dark climate. Supported on skis for transport, they always make use of a salvaged window or two to let in light and sometimes a small stove. I love the idea that a small town can emerge and exist for a few months each year, hovering over a space that remains empty for the other half of the year - a summer space.

It has me thinking of making one. As a folly, an impermanent, portable, winter encampment. I'd love to make one entirely of ice, casting the walls as thick slabs and fabricate the roof as a wooden deck. In the spring it would slowly return to the water, the roof transforming into a swimming platform, the shack's door - a ladder and an anchor.

I'll need some help...any volunteers?

A heavy dose of Dogtrot

Dogtrot [ dog·trot ] - a roofed passage similar to a breezeway; especially : one connecting two parts of a cabin. I'm a bit of a Dogtrot nerd - if that's even possible. I've long admired its simple form and the power of a single, well-proportioned void in an otherwise long, rectangular building. I've studied the building type in depth and offer you here an abridged 'design workshop', if you will. I particularly love knowing the origin story of this humble structure - see if you agree.

The dogtrot is a wonderfully versatile building typology that has endured differing building climates and cultures not only because of its utility, but also because of its simplicity and beauty.

Origins

While it’s hard to pin down the exact origin or antecedent of this building typology in the United States, there’s much evidence that earliest forms of dogtrots came into existence here in the lower Delaware Valley colony of New Sweden in what we now know as New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. It is believed that Swedish and Finnish settlers of North America in the mid-1600s brought a building typology know as the ‘pair-cottage’, from Northern Europe. These pair-cottages consisted of a pair of log cabins stationed side-by-side and joined with a common grass-covered roof. The Fenno-Swedish settlers were accustomed to working with large timbers and hewing logs for construction and as early settlers of the lower Delaware Valley it made sense that their woodworking skills were put to use in constructing their early homes.

The origin of the early dogtrot’s construction methods as linked log cabins is telling as well. There were two major limiting factors in the construction of log cabins - the first was the length of log that a team of men and livestock could handle. The second was the availability of such raw materials. Selecting logs of a length able to easily be moved into place, especially above one’s head, limited the size logs one could use to build the log structure with and thus the length of the walls. Equally, a log’s taper was a critical factor as the taller log sections yielded more taper. Accounting for these factors during construction ensured the log cabins remained small and one-story.

Once a log structure was completed, adding to it presented difficulty. In stick frame construction of the present day, additions are accomplished simply without much thought and in virtually any location. Lacking any way to modify the supporting walls of the log structures meant the only means of adding to the structure was to build yet a neighboring structure - again subject to all of the previously noted limitations. Building the second cabin only a few feet away would’ve resulted in a useless and dark intervening space. But by separating it a rooms’ width (12 – 16 feet) away it doubled as an additional outdoor, multipurpose room. All of this was accomplished with a simple, singular gesture.

Layout

The dogtrot plan layout is characterized by two equal rectangular shaped, single-story rooms termed ‘pens’; separated by between sixteen and twenty feet connected by a common, usually gabled, roof and a floored breezeway or dogtrot which spans the full depth of the plan. Each of the pens was accessed via a door opening onto the dogtrot separating the structures. The dogtrot behaved as an additional room. The functions of each of the flanking pens were usually different. One was used as private living space and the other as a kitchen and dining or any number of secondary uses: workshop, office, apartment, storage, tavern, or inn.

The intervening space, the dogtrot, served many purposes. Access between either pen and the dogtrot was simple and direct. Some historical examples omitted the floor in the dogtrot breezeway leaving bare earth. This created a covered place to service wagons - a sort of modern day carport. The more common configuration placed the floor coplanar with the interior space. In this way it functioned more like an additional outdoor room - a porch, a place to store farm implements and a place to sit out of the sun. This ensured a social status to the dogtrot as the central gathering point in these early homes.

The dogtrot design is known well in southern building cultures of the United States. It permeated southern pioneer architecture in part because it had offered an ingenious solution to the region’s hot climate. The dogtrot’s breezeway, positioned centrally in the plan, naturally created a cooler pool of air between the warmer interior spaces. This cool pocket of air could easily be drawn into the flanking pens by opening the doors at either end of the gables. In a time before air conditioning, one can see the draw of this passive cooling effect.

Chimneys

Providing heat to the enclosed ‘pens’, one chimney could be found on the gable ends of each structure. Early incarnations were constructed of wood, but proved extremely dangerous. Later versions were more fire-resistant and permanent built of brick and stone.

Porches

Many dogtrots included a porch along an entire eave wall. The porch usually had a shed roof with a lower pitch than the main roof and over time the exterior spaces of these porches were enclosed and apportioned to interior use.

Windows

Symmetrical window configurations were most common, with one or two windows per pen on each eave wall and two windows flanking the chimneys on the gable ends.

Attics

In keeping with the efficient use of space, full adoption of the attic space for both storage and even extra living space was common. This expanded the use of an often extremely compact building footprint.

Additions

The historical record indicates that dogtrots were of two origins. Those that began with one structure added a second and connected the two with the roofed dogtrot. And, those that began by constructing and connecting both pens at once.

Other additions took to enclosing porches, making each pen two rooms deep leaving essentially a foursquare plan, and even separated structures. The separate structure was popular in the south, where the kitchen would be housed in this separate building connected by a covered breezeway. This removed the largest source of heat from the living space and limited losses in the frequently devastating fires.

Construction

In the south, where ventilation and cooling are bigger concerns than insulating, dogtrots were commonly constructed on piers. In the north, fieldstone comprised many a farmer’s foundation because the glacial till was plentiful, required removal from fields used for crops and frost depth had to be taken into account. Stone provided a durable means of stabilizing the building’s support to ground not subject to freezing.

Materials

Log construction formed the basis for early dogtrots; the joint imperfections were filled with clay and twig chinking to keep out the elements. The interiors of these log structures used clapboards and board and batten wood finishes to conceal the roughly hewn logs. The limitations of log length and taper, as discussed earlier, had a substantial impact on the scale of early dogtrots. Equally, the raw materials available locally meant most of the structures utilized the wood from the surrounding forest - notably pine and spruce.

With advent of large scale lumber mills and the mass-produced wire nail in the late 1800’s the raw materials and methods of home construction transitioned away from log construction toward light frame construction which persists today as the most popular form of construction. Stick-frame construction being modular and infinitely flexible changed the construction requirements of additions and renovations. Sticks could easily create additions and loads could be transferred to the foundation by simply joining them together to create headers. Holes could be cut in walls and extensions weren’t limited to the size of logs.

Modern Dogtrot

With the necessity for additions no longer hindered by the dimensions and heft of the log, and social pressure to promote one's status via their home, the dogtrot succumbed to other more stately building types. Today those in the south who grew up knowing the typology often recall the dogtrot fondly, but at the time it was considered to be a very humble shelter. Which is to say, built for the poor. As such these homes didn’t correlate well with wealthy plantation owners and with time it gave way to grander and more sprawling architectural styles found in the south to this day.

As an architect interested in humble structures, I find the dogtrot to be particularly compelling – in its climactic response, its simplicity, its affordability and fort its flexible, integrated indoor/outdoor space. I think it’s why the dogtrot remains a viable and sought after plan for many.

While the climate of the Northeast, where I live and practice, isn't subject to the same stifling heat as the deep south, our winters and shoulder seasons beg for flexible transition zones between indoors and out. The dogtrot layout is the perfect corollary and it addresses this need elegantly. I think of it as an expanded mudroom, a place to store kayaks paddles and kick off your snowshoes under cover of weather. Pair it with a set of sliding screens and it's a screened porch. Add a fireplace and it's a sheltered outdoor dining area. Add benches and it's a living room or sleeping porch, or play space. The very lack of any strict functionality makes it inordinately useful and adaptable. Isn't that what our modern lives demand?

Interested in your own? I've developed a few dogtrots as predesigned plan packages, and more are on the ways - as always you can find them in the shop.

Design Workshop : The Beauty of Humble Materials

Humble materials aren’t costly or luxurious, but using them in residential design doesn’t mean you have to sacrifice interest or refinement. Many architects find inspiration in the humble beauty of simple structures dressed in plain materials that are used honestly. These materials don’t draw attention to themselves or pretend to be something they’re not. They’re chosen to modestly serve their purpose.

Design Workshop : Material Marriages

Some materials just belong together; in this video we look at a few of my favorites. Did I miss any?

Modern House Materials + Place Making

Today is one of those rare days here on the coast of Maine where summer bullies the usually refreshing maritime air into the 90’s. The wind has shifted to the southwest. The chickadees are mobbing and the mosquitos swarming. The cat can’t seem to get comfortable beneath his coat. My children head off to camp to whittle, sling arrows, and pond swim. I pass the woodpile and remind myself that I should be cutting and splitting my wood now for the winter which is never far. And keep walking. You know this feeling, or something similar, something familiar. You pause a moment from your busy life to observe and realize - this is summer. Or to think -the screen door slamming shut means warm nights. This is the definition of place for me, the emotional intersection of smells, sounds, temperature, everything surrounding you.

PLACE

When designing a home one of the critical components in the initial conceptual thought process is always to define place. Determine what it is that makes a place different and unique. Whether it's the forces that shaped the land, the geology, or the climate. What cues can you learn from the local architecture? How do people build and with what materials? Do the buildings sit lightly upon the land or are they rooted in the land? What are the natural site rhythms and weather patterns?

If you’ve lived anywhere for a period of time you probably know these things intuitively - the things that comprise place. They can be very subjective and they should be - that's good. You may not even realize what a local expert you are. Where I live on Mount Desert Island, in Maine there are a myriad of things to that inform my thoughts about place. The rounded glacial till and sharp black spruce tips, the colored grids of stacked lobster traps on lawns in winter, weathered fishing shacks and barnacled piers. This is a damp place, almost everything is covered in moss and lichen - green drapes gray and always the silver sea. Prevailing winds from the water twist and sculpt the pine boughs.

Local buildings are typically clad in one of two materials: cedar shingles or wood clapboards. Wood is abundant and inexpensive. Our native cedar is naturally decay and rot resistant and weathers to a silvery gray without finish or maintenance. The salt air corrodes and sticks to everything and the wind is ever present.

Are you forming an image of what this place is like?

WHY IS PLACE IMPORTANT?

Understanding this is key to design thinking and an important part of what distinguishes a work of architecture from a structure. Linking buildings to their surroundings and place makes them more meaningful and responsive to the forces surrounding them. What's truly wonderful about this is that this thinking is accessible to anyone of any means and any budget. It costs nothing extra to be sensitive to these things, to think like this, to define place and act based on your perceptions. By linking your home to your place in your time you’ve effectively said, “These are things about this place that I think are important and noteworthy.”

For example, shaping your home’s roof in a way that allows light in while protecting against the winter winds and shedding snow does this in a very simple and meaningful way. Working with the local topography, in an around trees and geology does this. Using local materials and a color palette drawn from the local flora imbues your project with deeper meaning. Through these simple gestures, your home can tell the story of the place you’ve chosen to build. What’s more, I would argue that your home will actually function better.

DESIGNING PLACE

I'll close with an example of a home I designed as one possible way of approaching design with respect to place. The overall design concept for this home was one of integration. Integrate views to the water, views to the forest, integrate sunlight into the deepest rooms and integrate the sloping local topography. I created three shed roof forms, one for the garage and workshop, one for the bedrooms and private spaces (the two story volume) and one for the public living areas. The shed roof forms were drawn from local shingled sheds used for storing fishing gear.

While developing the shapes of the structures and their engagement with the land and each other, there were additional subtleties that informed the overall approach I took with the design concurrently. Probably the one most illustrative of place making was the selection of materials.

MATERIALS

Most people, save for architects and builders, have trouble interpreting a floor plan. Lines drawn on paper usually have little corollary to a typical person's experience of a home. This gulf between the real and imagined is because spaces are difficult to represent in two dimensions and floor plans often lack color or indication of real materials. Two houses with the same floor plan can be rendered quite differently by modifying only the materials used. So how can you infuse the meaning of place via material selection?

Typically, I look to the site to conceive of an exterior and interior material palette. I find this substantially reinforces ties to a particular place and it's a simple shortcut you can utilize too. For this project, I started with simple image I had taken of a fallen cedar in a local pond. Note the contrasts I talked about above (here it's grays and browns) and the muted color range. This particular site had a number of oak trees present, which lined the forest floor with leaves - like tiny rust-toned scales.

By simply applying an overlay of this image on the actual building forms I created a set of basic rules for the use of color and material.

1 - Exterior: tough, raw, textured. The bark of the tree.

2 - Interior: warm and inviting. The warm browns + heartwood of the tree. Bark peeled back to expose the warm interior.

3- Accents: smooth, scaly textured. These would link the warm interior with the rough exterior. The fallen oak leaves.

4- Changes in elevation: marked by stone walls extending out into the landscape, linking and mediating steps inside and out.

THE RESULT

The tough, bark-like exterior rendered in the textured stained shingles is peeled back and cut away to reveal the warm wood interior. The interior is comprised of two types of wood which again mimics the variety of coloration inside the photo of the log, not one brown, but many (not too many!). Copper shingles are abstracted oak leaves in color and form.

The copper weaves its way throughout the house, but is used in very specific ways, to enclose the more solid parts of the house, on all flat roof volumes and it mediates the intersection of the house and earth (as flashing). The stone walls define changes in site elevation both inside and out and add another contrasting gray to the material palette.

As you become aware of the thought process that led to the design outcome, the meaning behind it should reinforce a sense of this place and the home's connection to that place.

Hopefully this information allows it to transcend any emotional response you have to the images (like or dislike) and the narrative should make it more alive. It certainly does for me and it makes the design process and selection of materials systematized and aligned with the greater design goals of the project.

Even without knowing the backstory, I believe, the building feels innately a part of the site and right at home. More images of this project can be found in my portfolio.

Cairns...and way-finding

Hiking is an obsession for me, an integral part of my life. And, despite my best efforts to integrate it into my children's lives my pleas for Saturday afternoon family hikes are usually met with groans of protest. Someday perhaps they'll recognize the same deeper connection to the land that I've found so satisfying through hiking too.

Living near Acadia National Park allows me access to challenging and uber-scenic hiking locations. If you've never visited Acadia, the bulk of the park is located just past the mid-coast area of Maine on Mount Desert Island. The island is a glacier worn grouping of granite domes perched at the edge of the Atlantic ocean. Here the raw granite meets the sea and is cloaked by spruce forest, fog and salty air. People carve out their lives here by understanding and exploiting these natural resources and the people who come to visit. Artists, fisherman, scientists, cooks, potters, boat builders, we're all here charting out our lives often against, but more often in concert with nature.

Hiking is an obsession for me, an integral part of my life. And, despite my best efforts to integrate it into my children's lives my pleas for Saturday afternoon family hikes are usually met with groans of protest. Someday perhaps they'll recognize the same deeper connection to the land that I've found so satisfying through hiking too.

Living near Acadia National Park allows me access to challenging and uber-scenic hiking locations. If you've never visited Acadia, the bulk of the park is located just past the mid-coast area of Maine on Mount Desert Island. The island is a glacier worn grouping of granite domes perched at the edge of the Atlantic ocean. Here the raw granite meets the sea and is cloaked by spruce forest, fog and salty air. People carve out their lives here by understanding and exploiting these natural resources and the people who come to visit. Artists, fisherman, scientists, cooks, potters, boat builders, we're all here charting out our lives often against, but more often in concert with nature.

The Bates Cairn

Aside from the physical activity and mental awareness hiking brings me, one of the things I find most rewarding about hiking is a deeper understanding of the world around me. I'm fascinated with the intersection of man's machine and nature. These are often forces which drive my architectural work, integrating buildings into their surrounding context, marveling at their weathering with time. This metaphorical tug-of-war is present everywhere, including the trails of Acadia.

If you've ever hiked above the treeline on a large mountain, you're familiar with cairns. Rock piles crafted by man to mark trails and pathways. They're necessary in locations subject to poor visibility and can mean the difference between a cold night spent on the mountain or a warm night off of it. If you hike a lot, like me, you may reach a point where they're like trees...they're a part of the landscape and you pay little attention to them.

I can't count the times I've walked between these simple landmarks, thinking of them as nothing more than markers along a path, but so often relying on them to return me to less foggy elevations. While reading a favorite column of mine in the Bangor Daily News called, 1-Minute Hike, I was surprised to hear reference to these markers as Bates Cairns. Designed by Waldron Bates in the early 1900s as unique trail markers. Each cairn is comprised of two support posts and one lintel spanning the posts capped by a pointer rock paralleling the trail. It's precisely Laugier's primitive hut and I think it's simply genius. The open topography and granite precipices here can be visually flat in poor weather and fog. It's easy to lose your way, but the degree to which these constructions stand out is remarkable. The simple act of creating a shadow beneath the lintel helps identify these as path points. And, their geometry is distinct and separate from a standard conical cairn. Which, in this landscape, would only work to camouflage them among myriad other rock formations.

Because of the efforts of Waldron Bates, I'm not only a thankful patron of all of the path making he accomplished during his lifetime but also a little more appreciative of his weather beaten constructs.

New Trails

This week marks the first full week of me bootstrapping my own, newly minted, design firm. The past seven days have been an emotional ride. Having to leave a place that provided me with many opportunities, fulfilling work, professional mentoring and some really good friends was a very difficult thing for me. Traveling new trails is difficult work but it's often the most rewarding. You're not sure of the destination, how long it will take to arrive, or if there's even a somewhere to go. Way finding has suddenly become a much more crucial activity for me and I'm searching in earnest for the next cairn.

30X40...?

Everyone asks, “What’s with the name, 30X40?” Here’s my answer…

Read More