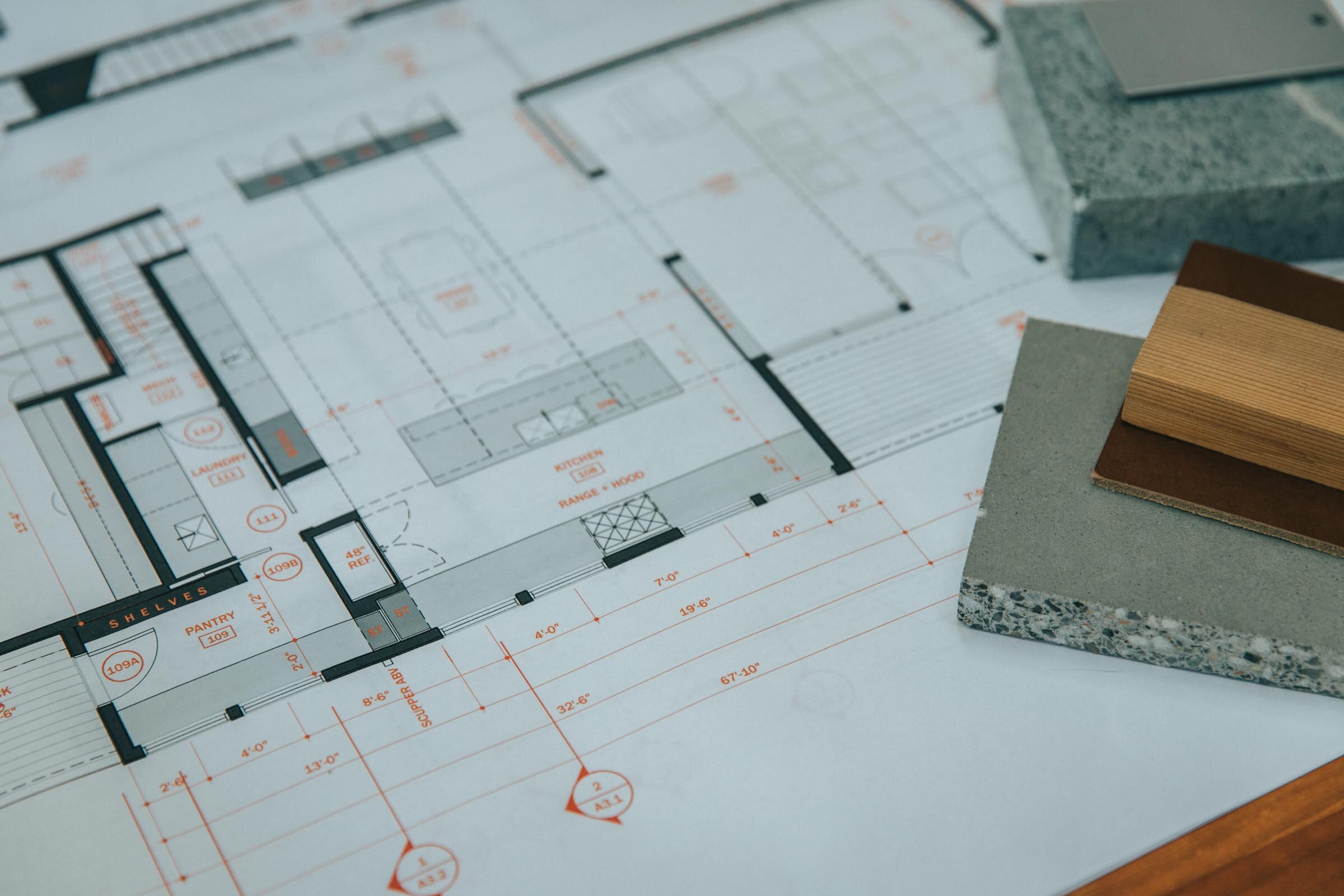

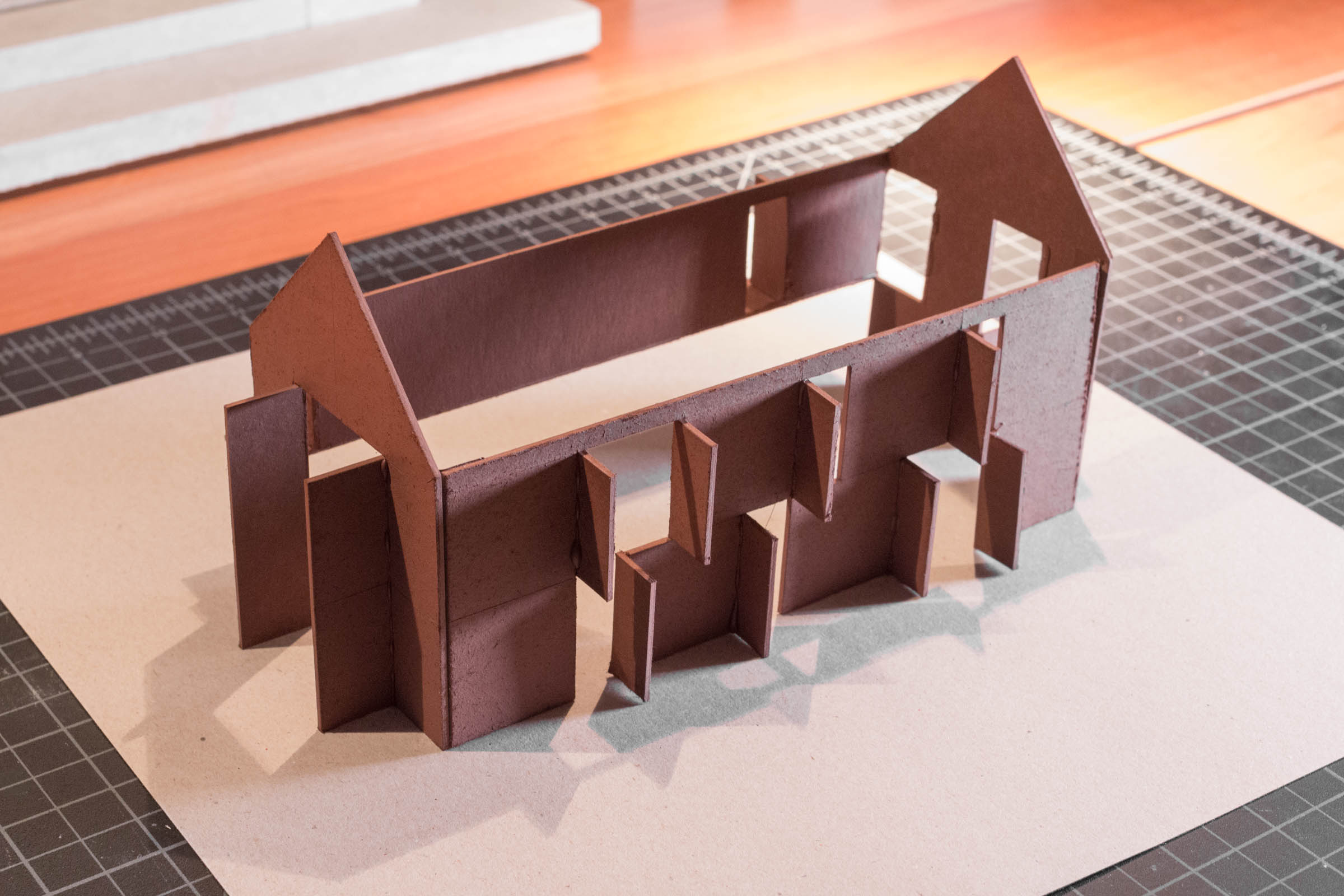

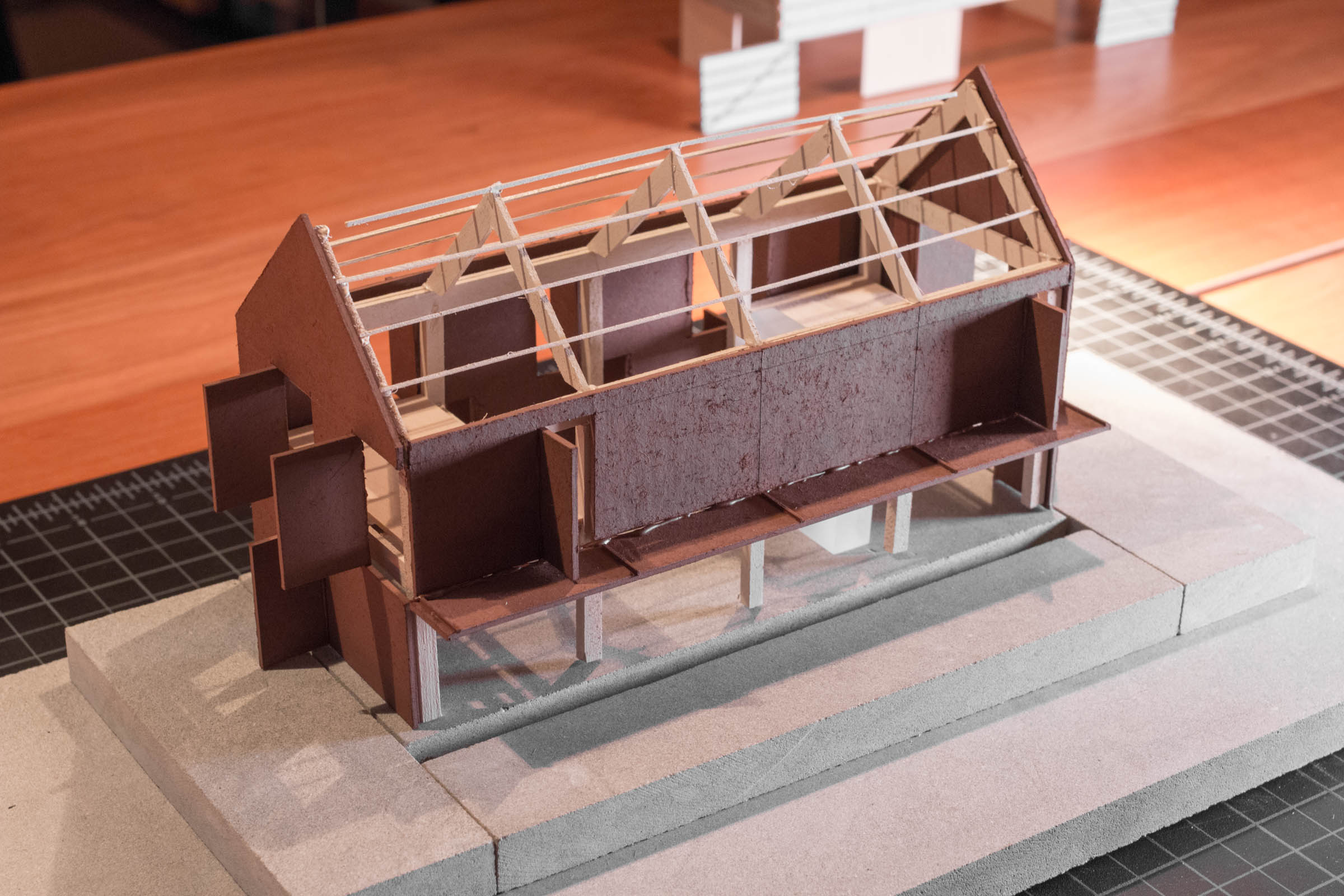

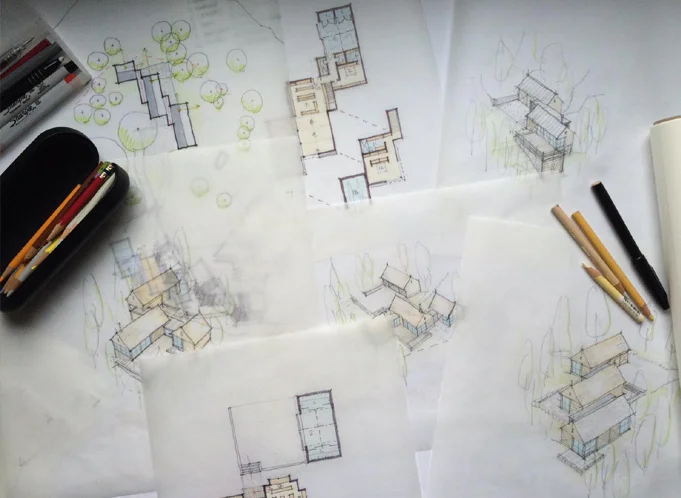

When you’re drawing plans it’s good to begin thinking about materials and systems too. It’s okay if you’re missing this information early on and you’re working on conceptual plans, but I like to begin with at least some idea of how I’ll be constructing the building. For example, is it a masonry exterior? Is there a glass curtain wall? Concrete, wood framed walls, finishes, each of these materials has a thickness and when you start to turn corners and add jogs or if you begin intersecting different buildings or surfaces, knowing what those materials are becomes really important when you’re drawing.

Your final floor plan drawing can be as general or as detailed as you’d like, but the more detail you imbue your drawing with, the more useful a tool it will be later on when you’re drawing column details or figuring out how the glazed wall meets the concrete retaining wall. When I begin drawing a plan, I choose a wall thickness and some basic finishes as a starting point. So here I started by laying out the exterior face of the stud wall on the superfine layer. For our squid cove project we actually started with a double 2x4 stud wall on the exterior spaced apart to prevent thermal bridging. So I offset the outer perimeter by three and a half inches the width of a 2x4 wall, and then a quarter inch for the break, then another three and a half for the inner stud wall. Then I offset the interior finish thickness of ½” for the gypsum wallboard, then on the outside 1/2” for the exterior sheathing and another inch for the exterior shingled walls, Now, along the way, as the pricing came back for the double 2x4 wall system it was a lot more expensive than we anticipated so we had to change it back to 2x6 walls. Now, because windows take a long time to fabricate, this change actually happened after our windows had been ordered and so those openings were fixed on the plan, we had to use those openings. So, we were left with this detail at the interior corners to resolve. Knowing the actual systems and sizes of everything around them allowed us to design the trim around the windows that not only matched the detailing on the rest of the project but made it look like it was an intentional design decision. So when you can, show finishes. They also fill in this fine layer of linework that makes the contrast between thick and thin really pop.

Lastly, sort of the icing on the cake, we have the annotations. Annotations round out the information you’re conveying on the plan. They’re really important wayfinding tools for the contractor so they need be very clearly organized. I use red text to make it clear that the annotations are a part of another ordering system and also something they need to pay attention to. And, the ink is just pennies more to print them in color, honestly…I think it’s so worth it. You could make it blue or gray too, whatever you choose. I like the red because it’s easy to point to a note and say, it’s noted in red, hard to miss, right? This works in both directions by the way, so if it’s your mistake it’ll be pretty apparent! Annotations describe things you’re not able to draw, they reference other drawings and details, and should all be on the ‘text’ layer so you can turn them on and off as needed for presentation or while you’re making other changes to the plan. Annotations grow over time, they’ll be basic at first things like room labels and they’ll get progressively more numerous as you make design decisions. Now, I’m begging you please…please, please…don’t use those hand-lettered fonts…just uninstall those from your computer. I use Franklin Gothic for mine, but anything but the chiseled pseudo-hand lettering should be fine.

You’ll know you’ve done this all correctly when you squint your eyes and you can easily see what’s important. Do the walls stand out? Do the annotations fade. As you spend more time looking for information, more information should become apparent, almost like a pull focus or slow reveal. Light lines of the hatches should be the first to fade and last to come into focus.

So that’s it, I hope it was helpful!

If you want my template, there are two versions available: