For me, the beginning of a new design project brings with it, in equal measure, both excitement and fear. Fear because the quest for design inspiration is an unknown path. The idea may arrive in an hour, a day, a month or, the deep nerve of fear: never. The architect Maya Lin, perhaps best known for her Vietnam War Memorial, likened her design process -- the discovery and inspiration -- to that of laying an egg. Her egg is an idea that arrives "fully formed" and it's the result of an unknowable amount of thought, study, sculpting , sketching and writing.

I'll admit to some envy of her process. Mostly because it results in a completely fleshed out idea, ready to develop into a coherent, beautifully articulated project. I console myself with the thought that she suffers the same anxieties all designers face.

I find my own search for design inspiration as elusive today as it was when I entered architecture school in 1991. It's an unpredictable muse. What I know now, that I didn't know then is that my ideas only come as a result of sketching. Much like writing, the ideas flow from the act of putting pen (or key) to paper (or pixel). The process of sketching is one that is taught early on in school as a means of thinking. It's a way to arrive at the genesis idea that sets a project in motion. Architects call this idea a ‘parti’. From the French, Prendre parti meaning "to make a decision".

And for an architect, nothing can replicate that moment when that idea arrives.

The Problem

I use sketching to document and synthesize thoughts about the site, surrounding buildings, the client, the necessary spaces, the climate, zoning restrictions, budget - basically all of the situational factors that represent the context of the architecture. While that seems like a lot to absorb, there are always certain themes that demand more attention than others. This makes the process easier for me as I dig deeper, a natural hierarchy begins to establish itself. There are building codes, restrictions, design review boards, wetland's commissions, budget, client proclivities - these are constraints that every project confronts. The goal is to understand all of the rules for the project and then set about creatively following them. It's often these constraints that can be the genesis for an exciting work of architecture.

A new project I've been working on is an interesting case-study for how this process works.

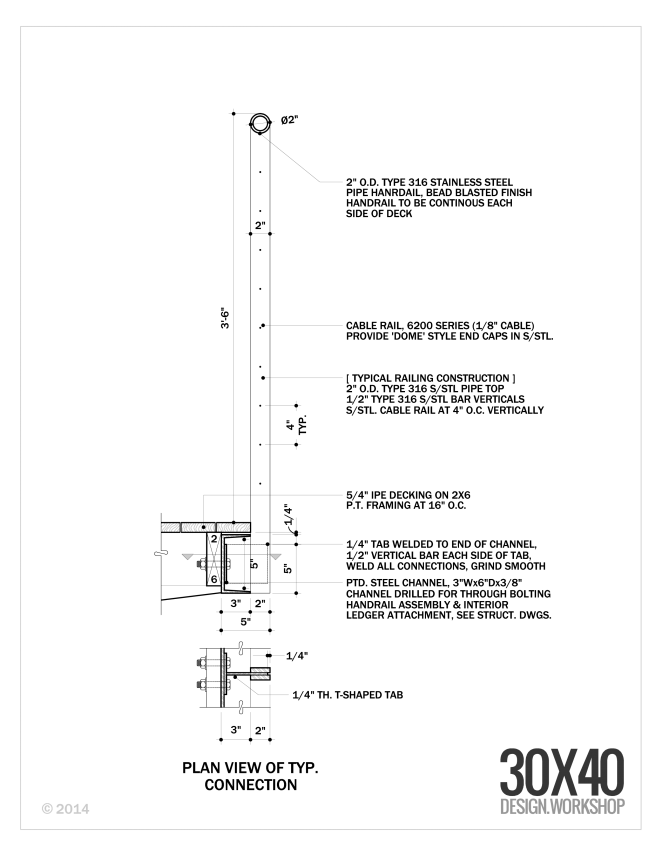

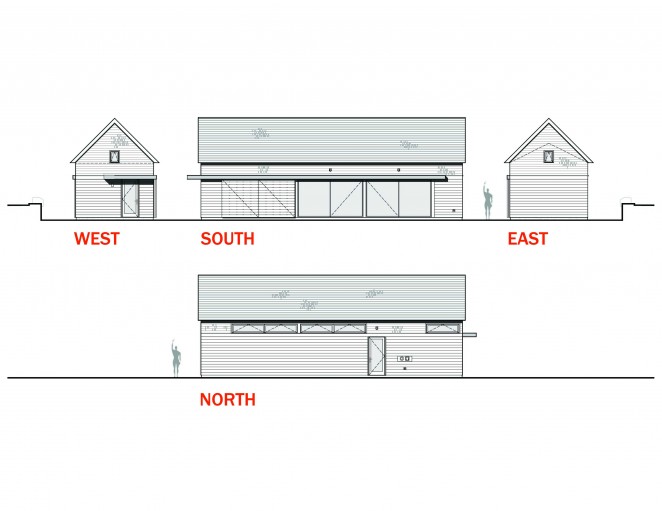

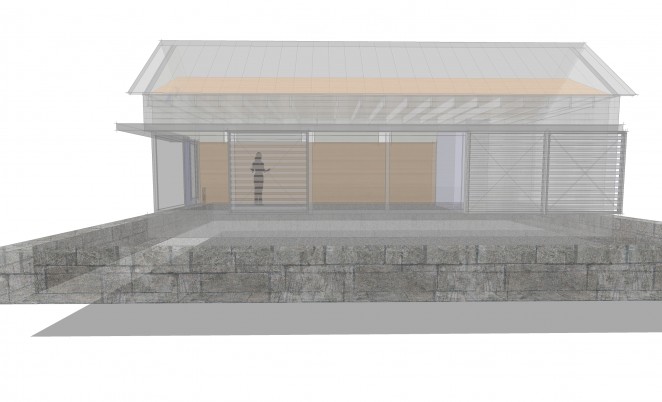

The client brief was to replace an existing, one-story dilapidated structure and double the leasable space of the property with retail on the ground floor and a restaurant on the upper level and an apartment on the uppermost level. The small 20-foot by 80-foot lot meant that the additional square footage would require a multi-story solution. Because it's in a business district it shares a property line with a neighboring structure to one side and to the other it looks out on a parking area and an unappealing, cluttered rooftop.

Seems straightforward, right? The building next door has windows along the entire shared property line and some of them serve bedrooms. So, legally we can't build right up against the property line and obstruct the bedroom windows. Given that the lot is only 20-feet wide, sacrificing any square footage would limit the leasable area and the monthly ROI for my client. The lot is also in a downtown business district with a Design Review Board which requires buildings to fit with the established character of the neighborhood, which is, buildings constructed to the lot lines. Add to this, the fact that the lot is oriented along a north-south line means collecting southern light for an upper story restaurant will be tough. It's a tricky problem, but there's one thing that stands out above all else when I think about how I'll organize the structure, that's where I begin to focus my efforts and my search for inspiration.

The Idea

Knowing that I had to preserve the exit pathway for the upper story windows of the neighboring structure reminded me of the complex network of foot paths that predominate the walkable European city. There, alleys were usually remnants of old pedestrian streets. And, while these pathways have become ever smaller as the cities became more dense and the land more valuable, the alley has persisted because they're essential for service, access, light, and air.

It was this realization, that I could create an alley between the two structures that was the spark that led me to the organizational design solution. But, this had to be more than just an alley. To maximize its functional potential on the small lot it had to provide the circulation for both my client's building and for the neighboring structure's exit windows, entry, exit, light, air - all of the things that an alley provides we can make use of. I won't get into the legal and code implications of actually constructing an alley between buildings, as it's complicated and somewhat uninteresting - let's just say it's a good solution to a complex problem.

The alley idea is a simple organizational concept, that helps me to begin laying out the building spaces on the site. But there are other ideas that I began to explore too and those informed how the building might consciously work to affect the environment around it.

In Part II, we'll discuss the visual inspiration and see the building take shape.